This episode is part of a special series celebrating ten years of Material Design. In the episode, Liam speaks with Bethany Fong, a Design Director at Meta who was a pivotal figure in the creation of Material Design.

During her time at Google, Fong was responsible for designing the first set of Material components (including Material’s signature Floating Action Button), and went on to become a design Lead on the team.

In their conversation, Liam and Bethany talk about the tactile nature of design, the importance of keeping a notebook, and how the heady early days of Material unfolded.

Listen to Design Notes on your favorite podcast app.

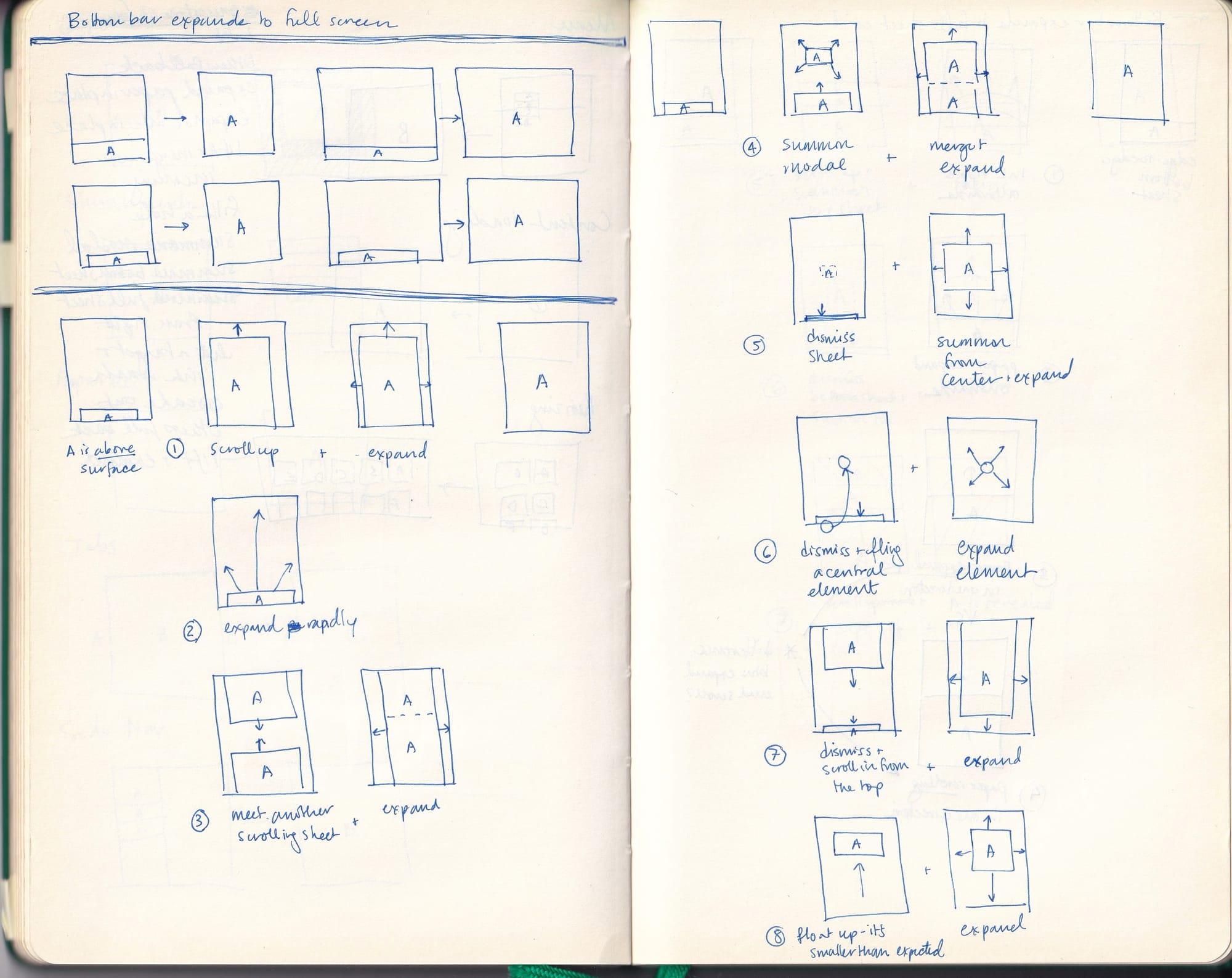

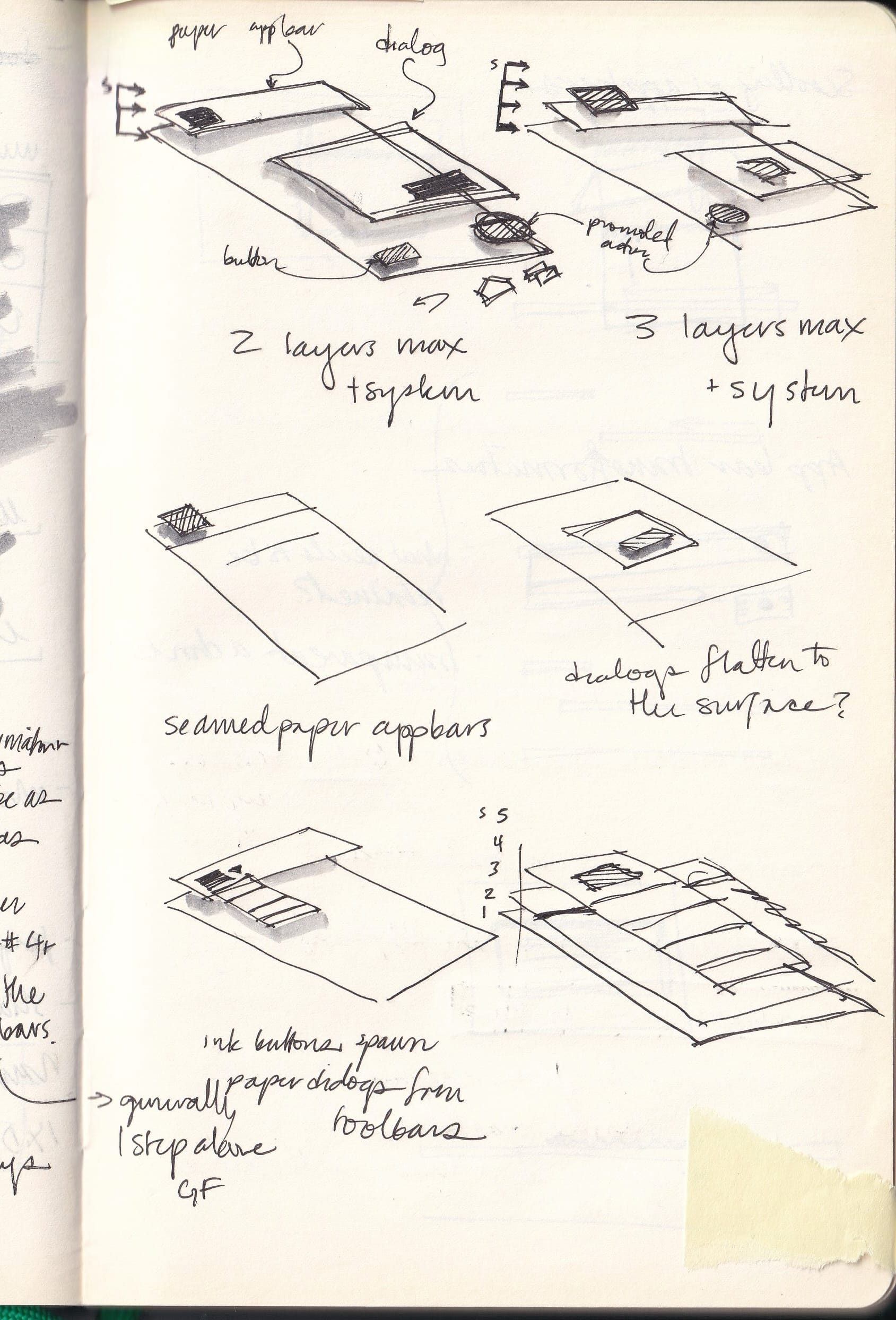

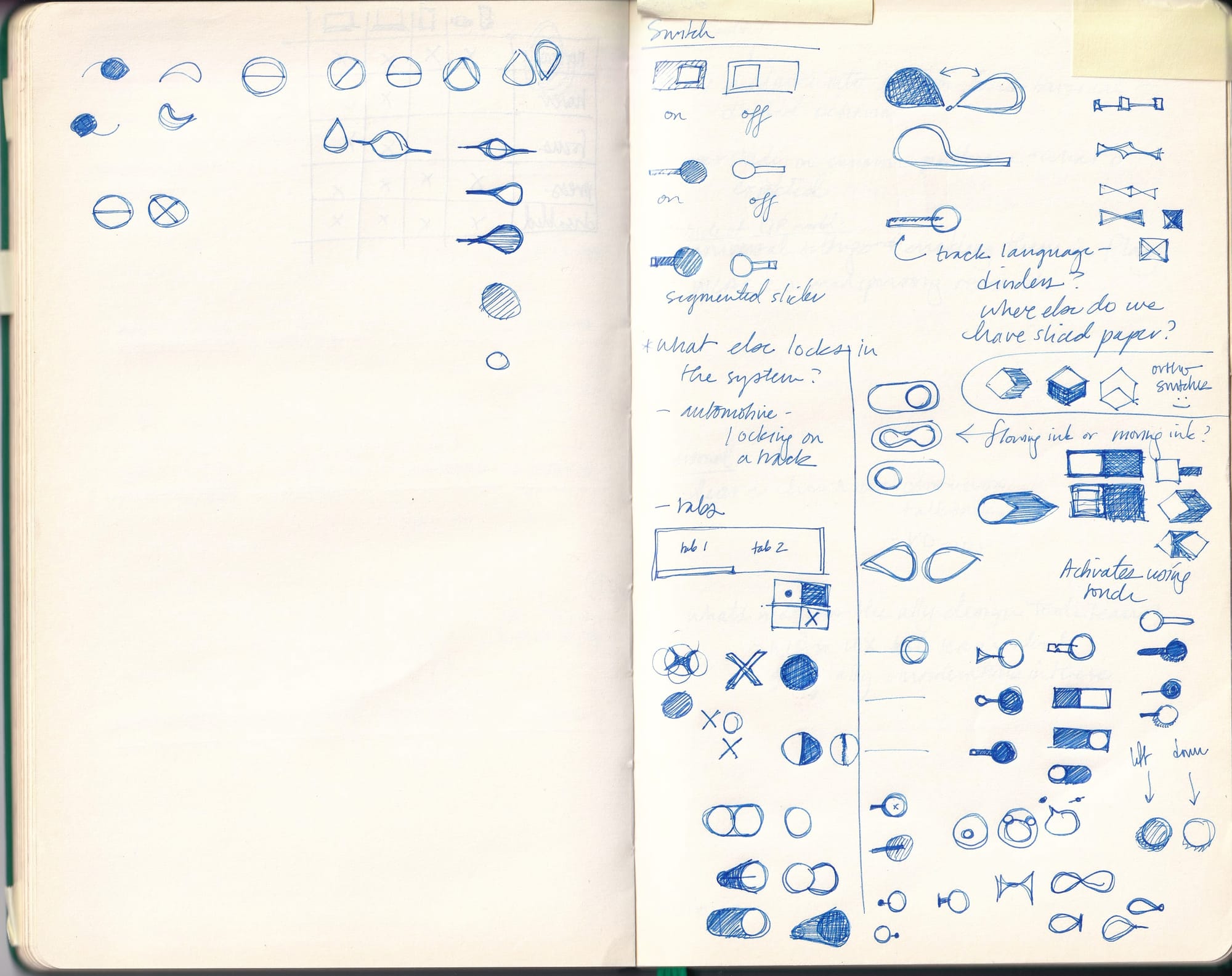

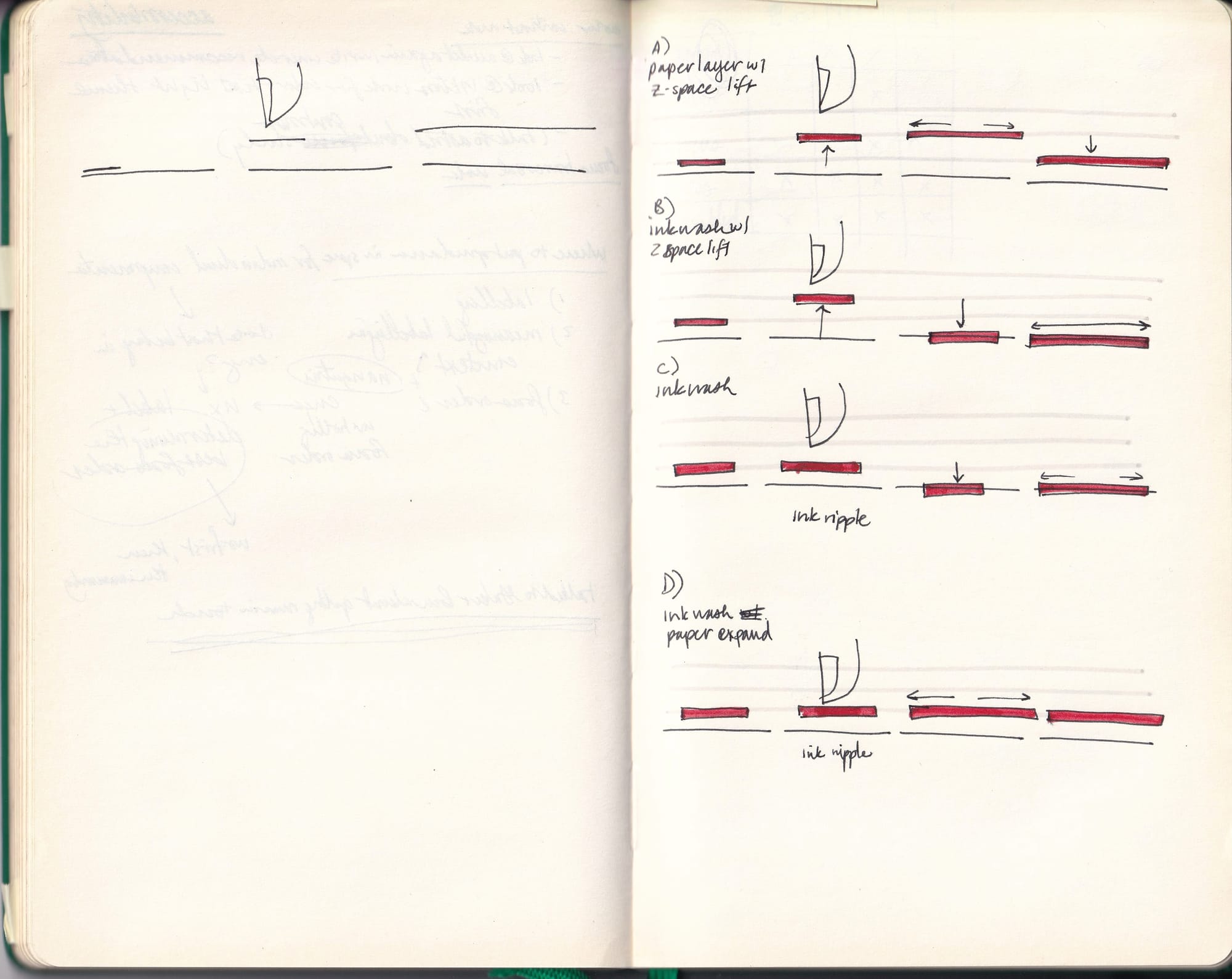

Pages from Fong's notebook while working on the first set of Material components

Liam Spradlin: All right, Bethany, welcome to Design Notes.

Bethany Fong: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

Liam: There's so much I wanna talk about, but I feel like upfront, I should tell the listeners that Bethany and I already know each other. We've worked together at Google on Material Design.

Bethany: When I was thinking about our conversation today, I was reminiscing and remembering the first time I met you, Liam. I think it was a dinner that the Google Designer Developer Experts were hosting after Google I/O, probably 2015, 2016, and you had done this beautiful work on adaptive design that our team was oohing and ahhing over, maybe unbeknownst to you, in the background, um, but I remember that the, the dinner was really chilly and we're all sitting together at the table kind of shivering. And at that point, the, the lead designer for material, Rich Fulcher, lent you his sweater for the evening. And I think that's when I knew that you would be joining the team eventually.

Liam: (laughs) My fate was sealed.

Bethany: Yes.

Liam: It's so funny, like I'm sure that if my friend, colleague, and former manager, Yasmine (laughs), is listening to this, she's laughing because I've historically had such a bad track record of dressing appropriately for cold weather (laughs).

Bethany: (laughs)

Liam: So she would say, like, "Of course, you were shivering."

Bethany: (laughs)

Liam: (laughs) But, yeah, I ... Now that you say that, I'm, I, I do remember that back in the project Phoebe days and I, I, like, gave a little talk. I was, like, so hyped to talk to you all after seeing you on stage with Material Design and being, like, so inspired. It was really cool.

Bethany: Oh, we were so excited to talk to you, too. And, and come to think of it, you know, that sweater that got draped around your shoulders was probably Material Design swag, so just a real early indicator of where you'd end up.

Liam: (laughs) Always headed in this direction.

Bethany: Yes.

Liam: (laughs) Okay. So reminiscing aside, um, I wanna know ... You ... We worked together for a handful of years at Google, uh, but now you're doing something else, and I wanna hear about what that is.

Bethany: Well, these days, I'm working at Meta. I'm actually leading a design systems and visual systems team, uh, that, um, brings the Meta brand to life across, um, Meta's products.

Liam: I always like to ask a question about people's journeys. So how did you get there? How did you get here right now?

Bethany: (laughs) Um, how far back do you want me to go?

Liam: I like to start at the beginning, but you can be editorial about it.

Bethany: Okay. Well, beginning, beginning. Um, I grew up in the mountains from, uh, Colorado and then in, in the Sierra Nevadas, really close to Yosemite. Um, and so I've always had kind of a sense of the landscape and beauty and grandeur and the ecosystems that undergird the world around us. Um, and I was also a really creative kid, like I drew a lot, I read a lot. I've tried every craft known to mankind at this point. Um, so I've always had my hands on things as well, so kind of creating and then responding to, to the, the landscapes around us. I think that's what eventually drew me to design as a course of study.Um, I, I went to Stanford for undergrad. I switched my major a couple of times, started with bio, because I was just so, uh, enamored with systems and ecosystems, but I found humans to be interesting, too, in the mix. And so, um, switched to human biology, which kind of examined more of the effects of, of psychology on, on biology, but then switched once more over to product design, basically (laughs) just one winter break when I was looking through the course catalog and realized that I resonated with every single class that was listed under the, the product design category. And, um, maybe it was a, a foolhardy move, but I followed my heart, followed my gut at that moment, and just decided, "Yeah, I, I'm gonna go for that. All of that sounds amazing."

Um, so, um, you know, kept, kept leaning into my kind of intuition for, for beauty and, and making things and making that choice. And, um, and after I graduated, ended up, uh, kind of doing a couple of, of random jobs as, as I wove my way towards Google. So, um, I had a long-standing interest in designing for accessibility and making the world work for people with disabilities a little bit better. Um, and so I ended up working with a, a socialization program for kids with disabilities for a, for a period of time. Um, ended up getting a design internship for a Korean company and then, um, worked at Google starting in 2011. So, uh, began on the Android team.So, again, systems, always drawn to systems and ecosystems and, and thinking how all these things work together. And, um, worked on accessibility, Android TV, and, and eventually Material Design starting in 2013. So, um, I ended up being at Google for about 10 years. And my pithy way of summarizing my time there is that I, I ended up redesigning Google three times via Material, the Google material instantiation, and then Material 3, which was shortly before I left to go to Meta.

Liam: There's so much there to unpack. Um, I think something that stood out to me was the jump from human biology to product design. First, that struck me as like, "Wow, that's a huge jump."

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And, and also, like, it sounds like there is some kind of natural resonance there. But then I was also thinking about, like, I'm a big believer that design intersects so much with our humanity and the concept that, like, something can be systematic and yet still have a mystery. I'm wondering, like, where would you see that through line?

Bethany: Well, let me, let me just talk a little bit about the jump from human biology to product design. And I think gets at that a little bit. Um, one thing that was unsatisfying about human biology is that it felt very passive. You know, I could read studies about populations, I could hear lectures about, you know, ethnographies, um, but it felt just like I was sitting back and observing and not acting in the world or perhaps affecting humans via (laughs) their biology or, or what have you. Um, and then I felt that design kind of flipped that o- on its head a bit, where I, as a person with a perspective, and particularly an aesthetic perspective, could go out and affect the world with knowing what I know about humans and trying to apply the science of psychology, um.And so I think that, I don't know, made me feel a little bit better about myself or felt like I had more to offer the world via that field, um, where I could have this methodology of going and, and affecting change. Um, so I think that's, that's kind of where the flip happened for me.

Liam: You know, obviously, the reason that we're here today is to talk about the fact that Material Design is 10 years old. You were a huge part in creating, revising, evolving, leading Material Design. Um, I want to get into, like, w- where you were in that design journey 10 years ago and what is your recollection of that time and how Material started to emerge?

Bethany: Yeah, of course. And I will say I'm really grateful, Liam, that you chose me to interview for this podcast. You could have chosen any number of folks who were involved from the early days. Um, and, and there were so many smart and talented people that were involved. So just laying that out there first. I was just one of a team.

Liam: Sure.

Bethany: But in, in 2013, I was 26 or 27. I was a junior interaction designer on the Android TV team. I was working with, uh, Hector Ouilhet. And, um, I, I remember Google had just updated its suite of web products, which included Gmail, which was a s- semi-new entrant. Um, and it was all updated to this new design language called Kennedy, which introduced a much more streamlined approach to design across all of our web properties. And, um, it was actually my very first week at Google when project Kennedy was announced, and I remember sitting in a cafe that had been turned into an auditorium, seeing this design-led project get announced, and I was this junior designer joining and be like, "Wow, this is amazing. You know, design's getting the spotlight."But then all around me, I heard all these kind of mumbles of dissent from the engineering culture and, and seeing so that comments float in on the, on the announcement of like, "What's all this white space doing in our UIs? Like, this is just such a ... This, this doesn't make any sense. Why do we care so much about type?" And I realized, like, "Oh, okay, this is, this is gonna be a challenge to, to push change forth through this org," but, um, but it happened, you know, Kennedy launched. It was a, a nice evolution of the design language.

And so, um, following on from Kennedy, a group of design leaders from Google decided to set their sights a little wider, um, and that included people like Matias Duarte, Nicholas Jitkoff, Jonathan Lee, John Wiley, and, and many others. Um, and the goal was, how do we unify both mobile and web design languages? How do we best serve this Android mobile operating system, um, that's now under our purview and, and elevate the experiences that are on it? Um, and it had really intentional graphic design and motion design roots. Um, those disciplines were part of the team from the very beginning.Um, and so at that time, uh, Rich Fulcher invited me and another interaction designer, Dave Chu, to join this very small, fledgling interaction design team, it was just the three of us, to tackle what might we do with this language or, or with the scope of this project. And so we divided and conquered. Rich took navigation and patterns, Dave took containers, and I took all the components for the system, which, now looking back, was, uh, maybe a little bit of hubris on my end, but honestly, I was just too, too junior to know better that doing all the components as, as one designer was a lot to, to take on.Um, so, yeah. So that's how I started to get involved in kind of the, the nucleus of the project. And, um, we worked furiously from 2013 all the way through the launch of, um, what we then called Material Design, uh, in 2014 at Google I/O that year.

Liam: You worked on components which are, of course, like one of the most iconic parts of the system. It's the most tangible, perhaps, like, aspect of the system, um, that people interact with. What stands out to you from doing that work?

Bethany: I recall that working on components felt very much like mechanical engineering to me. So I had studied mechanical engineering and product design, um, which was actually not an HCI-based program. It was all based on physical product design. And I remember, as I was kind of burning through my list of components to work on and considering how they all fit together, I would actually have these kind of pictures of mechanical objects in the back of my head, imagining how they would translate into zSpace, although little kind of Rube Goldberg machines that a UI was starting to turn into for me. Um, and it really helped the, the concept of these components to click, uh, the idea that I was making all these little machines that would power UI. Um, and I, I think that actually fit very nicely with the kind of, uh, tactile origins of Material Design. I mean, right there in the name, material, thinking about material objects and, and material properties that would help drive, um, understanding of UIs.

Liam: Yeah, something that really struck me back then as, as a designer out in the world, like a beginning designer, was, was like, search-, like drop shadows have been around for a long time, but Material Design made it convincing. And I think it is because of that influence from both graphic design and the mechanical knowledge of how something in that space would work and also thinking about the interface as a system. Like, I don't think that, at least, to my knowledge, in interface design at that time, that, uh, that level of creative systematization was really widespread yet.

Bethany: Yeah. I, I mean, I would agree. There was ... There's certainly things like design patterns or design languages or, or even, you know, sprites and sticker sheets that were used to construct UIs. Um, but it felt very bold and rightly comprehensive to tackle the problem from that perspective.

Liam: Can we talk about the FAB a little bit?

Bethany: My favorite, FAB. Sure.

Liam: It's something, it's something that really feels like material invented and even companies that would claim not to use Material do often use a FAB. Where did that come from?

Bethany: Yeah. So the FAB, for those of you unfamiliar with acronym, stands for floating action button. It's the little circle that you often see with a, with an icon inside of it or now it's been expanded to an icon plus a text label, yay, accessibility, um, that is, that contains usually the hallmark action of a given app. It's meant to be really prominent, thumb-friendly when you're on mobile, and just gets you to the action that you need the fastest. Where it came from is it actually arose out of, I think, two parallel pathways of work.So, um, on one side, uh, Zach Gibson was a visual designer on the team was working on visual hierarchies with, with Christian Robertson, who's the creative director, and coming up with all of these really beautiful color-blocked graphic layouts, um, rectangles with high contrast, bold blasts of color, but also starting to experiment with focal points within those compositions. Um, and some of those focal points were circles that ended up at the intersections of sheets or in corners or just in interesting places that created nice designy tension in those layouts.Um, in a parallel path, I was working on information hierarchy and how to organize apps in a way so that users would find it as easy as possible to just complete the task that they were doing.

Um, and so I remember there was this one crit where we were looking at these giant plotter printers of these layouts, you know, all up, tucked up on a phone board, and starting to realize that, you know, these circles could actually be something really interesting and important for the system that what if I took my hierarchical pyramid of buttons and said that for, at the very top, that the most important action of any given app could actually be placed into this visual focal point.And the idea just kind of took off from there. Um, it worked with a number of the kind of early adoption use cases that we were testing with, um, of different apps across Google, um, as well as some, you know, fictional case study apps that we had, had used to also test our ideas. And it, it felt really right that the actions that we'd be celebrating the most in the interface, the ones that were closest to the user's face and thumb in, in the zSpace layer would be the ones that were most generative and creative and, um, would help the user succeed. And it just kind of took on a life of its own from there.

Liam: I think there's a really nice through line there with the kind of, um, graphic design influence that we mentioned before, that something so powerful could emerge from creating this focal point. You use the word tension ...

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... which I love, because I think often when we think about systematizing design, it feels like a bit, um, mathematic, that a subjective experience like tension in the composition of a screen, um, doesn't always have that much room to breathe and to flourish and to become something so important.

Bethany: So there is a concept that Matias Duarte like to use. And he says, "Does it tickle the lizard brain?"

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Bethany: And it was, it was a, a, a funny way of describing the way that (laughs) this big concept of art and technology and design intersecting in Material where we'd use all these cues of physical reality in order to communicate some difficult digital ideas, um, you know, like the structure of your inbox and, and the state of all of these items within it. And so I think Matias was, was saying that there is a certain simplicity, um, that needs to come across where people have to just intuit what's going on on the screen using kind of their instinctive lizard brain.Um, and so I think when we're thinking about tension, um, that visual tension that's present on screen of this item that's floating above other things, like we're, we're relying on that cue. And it's a very simple cue of there is something on top of something else, therefore it is important, and using that to drive, hopefully, user success and engagement.

Liam: Yeah. And just building on that tactile element for a second, I know from seeing the videos and behind the scenes like the paper cutout icons and the lighting rig with all the different layers of elevation, it seems like there was a lot of tactile exploration in creating this before it could be modeled into a digital system. And something that stood out to me when we were talking about your journey leading up to design is also that you've been so involved in crafts and enjoying, like, the tactile aspect of making things with hands. And I'm wondering, first of all, what, what role did that play for you then as you thought about these, like, little machines of components, and also, what role do you see it playing now in design? Um, I'm curious, like, where that is these days or where it can go.

Bethany: I'm curious, too, Liam (laughs).

Liam: (laughs)

Bethany: Um, well, I've ... Yeah, I mean, you're absolutely right, that being hands on and the tactility of making things has always been an important part of my process and it seemed to be a really key part of everyone's process when we were making Material. Everyone toted around our own little notebooks. We were all sketching furiously at any given moment, um, is very natural for, you know, in a design crit, someone to hold up their, their notebook and, and show their page. Everyone be like, "And, and this is how I would synthesize that idea." And there was a real, um, like, fluidity and ability to articulate visually, which I think is a little bit lost right now.I mean, we've ... I mean, with the rise of remote-first work and we're often not co-located in the same place, um, it's, it's become more important that you have to communicate your thoughts, um, digitally basically immediately. And so going to that sketchbook as, like, a first place to work out an idea, I, I think, isn't as, as natural anymore. Um, it feels faster to just go to the Figma or go to the Google Doc and, and start writing things out or attempting to, to sketch things out in whatever, um, you know, Google Sites (laughs) or what have you, which is super tough.Um, I, I still think that tactile exploration is important. I think I, I haven't been able to kind of thread the needle for how we get from, um, or how we more readily prototype experiences in space. I think of all the spatial computing paradigms that are becoming much more mainstream quickly, and yet there is, uh, an inability for designers to articulate their thoughts about those spaces very quickly right now. Um, I mean, just as we're talking, it's striking to me, I have not yet seen any designer ... I mean, maybe I'm uninformed, but I haven't seen any designer even, like, hang sheets of paper around their workspace or their face in order to try and understand, like, what feels comfortable, what's legible, what's readable at certain distances. All of the prototyping has been digital or involves, like, putting a headset on and off your face, um. And so I think, you know, maybe there's, maybe someone's tried it and it just hasn't worked. But if we're going to be moving into an age of, of spatial computing, then I think it would behoove us to understand first how space works and how, how information in space around us would ideally behave.

Liam: Yeah. And, and again, how it does behave with our bodies. I mean, going back to the original material metaphor. But also, there's something interesting, like in the, in the conversation about sketching and how it's, like, hard to sketch in slides ...

Bethany: (laughs)

Liam: ... or docs or something. There's something like ... Sketching, at least for me, is like places constraints on what I can produce in a healthy way because there's, like, a sense also of proprioception, like the use of the tool that is my hand is really intuitive because it's attached to my body, but it's constrained enough to help me get a focused idea across, which I think is, like, hard to do in the tools that we have and perhaps even harder to do now that, now, like, with the prevalence of tools that really understand interface design specifically. They're so focused on that ...

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... um, to the exclusion maybe of something lower fidelity.

Bethany: Yeah. I mean, I think we've ... (laughs) Material Design has also helped create the world that we now live in, which is where design systems are everywhere, and it's so easy to just go into a program and start playing around with a sticker sheet of incredibly high-fidelity components that, you know, may turn into a UI right away or might be the wrong combination of tools and mechanics in order to achieve a, a given task. Um, I think we've, we've all seen UIs that feel like it's just been copy and pasted from a bunch of sticker sheets and those aren't very satisfying or exciting. Um, but, yeah, that's, that's basically the sketching tool that we have right now, sketching in things that look real, which is hard.

Liam: You mentioned that Material Design has shaped this world of interface that we now live in.

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: How has that looked to you both, both during Material's formation and also now that you're working in Meta, leading a completely different system?

Bethany: Well, so much has changed in the last 10 years that I think Material has helped normalize. Um, so when we were creating the system for one, it was very novel that web and mobile would be considered as part of the same design system. Accessibility was also a, a growing interest amongst design. Um, I actually helped to write the first accessibility design guidelines for Android as well just about a year before I got started on Material. So there was not that much informational material out there, um, particularly for the mobile space, which we were kind of inventing at the same time. Um, and ... I mean, the category of design systems, I think, was really put on the map by Material.So now, um, it seems to be the norm that any, say, like, any new designer joining a company will immediately have at their fingertips a unified web and mobile design system that has accessibility built in from the very beginning, and that is a beautiful expression of brand and is well considered. All those things were not the norm 10 years ago. Um, and I think that's progress. I think those are, um, those are good norms to have established, um, with, you know, doing our part via Material, um.And so now, um, as I'm leading a new design system team at Meta, uh, I'm trying to continue to build off of that norm and also improve it and, and push it into the future. Um, of course, it is, it is difficult with the realities of building software and resourcing to be able to build a fully featured design system with mobile and web parity and, and be, you know, taking risks aes- aesthetically. Um, but I know that there's also still much more that can be done with systems and, and within systems, it's still a very rich field of exploration for me.

Liam: I'm really interested in this part of, like, a new designer showing up to a company and they have immediate access to this well-considered system that is so, yeah, rich in features and consideration for all the things that you want the system to do. Something that I, I think we've heard over the years sometimes is that designers feel that design systems can be stifling or ...

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... limiting or a constraint on their creativity. And I'm really interested in that, particularly because I, I recently had a conversation with a friend who is not in a creative role but has been tasked with leading creative people. And we have been trying to figure out, like, how the consideration that has gone into the system and the rationale, uh, is conveyed in a way that can make a new designer feel, you know, in tune. I'm wondering how you think about that leading a design system or design systems team, how is rationale communicated, how is the subjectivity of the system, um, kind of made apparent to, to folks who, who might, without that knowledge, feel, uh, too constrained or outside of the system itself.

Bethany: I think having well-written guidelines makes so much of a difference. Less is more where you'd like to convey just the ra-, right amount of guardrails with using a system or how the system is intended to be used together, but not overly constraining individual decisions, um. And I think what can counter, what can help counter the feeling of constraint and dos and don'ts are ... I've a number of different tools in my tool belt. You know, great examples that demonstrate how a design system can be used flexibly or places where the design system has been broken in a really new and interesting way that actually helps advance the entire system overall. I think it's actually quite powerful for product teams to see when a design system see, teams has said, "Hey, look at this. This is new and it wasn't really using our system, but it was in, like, the spirit of the system." And so we were, we were gonna celebrate it and embrace it, um. So great examples.And I also think how we show up as people and as a team and as individuals when talking about the design system really matters. I have to say, I have yet to meet a successful design system practitioner who is draconian in their approach to design systems.

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Bethany: Um, most people who I've worked with in this field are very interested and curious about how a design system is working or not working or is overly constraining for their users. And I think there's a certain amount of empathy and permission that we imbue as design systems designers coming to that conversation that's really important to, um, have, have using the system keep feeling right, feeling good, and not like it's overly constraining.

Liam: I wanna zoom out from there to design leadership and designer leadership. I wanna know about your experience as a design leader and as a leader who is a designer.

Bethany: I like how you're kind of playing around with the words and, and breaking up the concepts of designing and being a design leader and being a leader, um, because, to me, those are, being a designer and then being a leader are skill sets both to be developed, um, and then in the right moments combined for, for maximum impact. Um, I think there's, there's definitely been different parts of my career when I've focused more on practicing the design aspect of the work, and then I think more recently, it's been more practicing the, the leadership aspect and, and learning how to set a direction for a team, how to motivate a group of people, how to communicate care, create a safe environment to take risks, but then combining it all as a design leader, I think of what is my unique perspective that I'm bringing to the organization as a whole.Like, looking around me, looking at my cross-functional partners, what do I know that they don't? I know a ton about aesthetics, about human psychology, about perception, about what feels right for users, what's gonna resonate and what's not. And I view it as my role to communicate humbly but also with confidence the directions that I think our product should go, keeping those aspects in mind.Um, it's also my role to create space for my team to push forward in those areas, um, and to give permission that we can do those interesting and different things that maybe other people aren't always asking us for, but we see that there's value in. Um, and so it's my role to kind of set the horizon line for the team, 'cause if I'm not talking about the ways that we can push forward and what we can dream about, there's not as much permission for the rest of the team to do that either, like maybe there would be an outspoken person here or there who could help drive the team forward. But I view my role as setting the tone and helping us understand that we can push for change, and that's okay, and that is what I'm expecting of the team and what hopefully the org is expecting of us as well.

Liam: I think it's also critical to pull out that point of your unique perspective on design and the interdisciplinary nature of that. I think one thing that I hear over and over again on Design Notes is like, "Well, I had a weird journey to design, and first, I did this, and second, I did that, and third, I finally got to design (laughs)."

Bethany: (laughs)

Liam: But I think, I think that often goes overlooked. I'm, I'm wondering how you see that showing up as a leader, like within the team or within the, the broader group that you're working in.

Bethany: Mm-hmm. I think another word to describe what you're saying is intersectional, that there's ... Like, each of us as designers or as creative people are bringing so many different aspects of our identity and our lived experiences to the work. And I think that's so important to, you know, be comfortable with expressing and, and helping to inform the creative work, um, so that it can be strengthened with all of those perspectives. Um, I know, for me, like, my design journey is inextricably linked with being a woman in tech in, in very generally kind of male-oriented spaces, um, being a, an Asian American woman in tech, uh, being a leader and, and learning to find my voice, learning to understand the perceptions that people have of me and then break those or, or use those (laughs) accordingly, or, um, just be able to navigate through those perceptions of me but also of my lived experiences having, you know, being an, an Asian American woman in, in technical spaces. Um, and I would hope that any creative would be able to draw inspiration from and be able to pull from the emotional realities of their experiences when making new things for other people, um, 'cause we are, we are making things for people, not for robots and, um ... Well, I don't know. Maybe with AI, we are making tools for robots, we'll see.

Liam: (laughs)

Bethany: Um, but, yeah, I, I have to, maybe not strive to remember, but it is important for me to remember that, like, myself as, as a person is making things for other people. And, I don't know, that's just the point of connection that I have with them through the UIs that I help design.

Liam: Yeah, that there's some subjectivity, both in the input and the output, but somehow being interpreted through the technology. I wonder ... I mean, I think looking around, I think it's easy, like, working all day around the word system to, even with an awareness, to, to kind of lose track of how those subjective inputs of your experience are showing up directly in the work.

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And I wonder if you have thoughts about how people can be more intentional about that.

Bethany: That's a really good question. I think one concrete example, just going back to the FAB example of where my opinion or subjective experience has, has played a role, was the FAB where it was a risk to pull out a single action and literally, like, lay it on top of the rest of the interface, but I thought it was important to celebrate a positive action that users can be doing with the apps. Um, and with these services, I wanted to basically create a, a shorter path towards (laughs) making people's lives better by, by going in and, and interacting, um, in a way that they felt agency. It also pulled from my perspective of working with, uh, kids with disabilities and this accessibility perspective of how do you create greater focus and help people feel successful faster. And I am willing to take that risk on their behalf, um, on all of our behalfs, to, to create that, um, that single focal point, and then the fact that I was bringing those constraints or ideals to the UI, I think, did make it better. As with any sort of design, more constraints, I think, make a more interesting end product.

Liam: Right. And, and thinking back, it really stood out to me then also that, that the FAB was explicitly for positive actions.

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: That you shouldn't do something destructive with the FAB.

Bethany: Mm-hmm.

Liam: Which was ... Which is really, like, great (laughs).

Bethany: (laughs)

Liam: I don't know what else to say. I found that, like, really, really nice.

Bethany: Yeah, it was one of the more opinionated, I think, aspects of, of that work of ... Normally, we, as systems designers, don't say a lot about what should be going into buttons or not into buttons.

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Bethany: We just make the button and then move on.

Liam: (laughs)

Bethany: Uh, but this was a place where I, I did have a lot to say.

Liam: Yeah, that's awesome. I, I wanna close especially because you brought up making tools for robots. I mean, there's a lot ... (laughs) Speaking of tension also, there's a lot of tension in the industry right now, but I remain optimistic, and I would like to know what you think is coming. What, what do you want the future to look like for design and what do you think it will look like?

Bethany: Oh my gosh, Liam, what a huge question.

Liam: (laughs) Maybe, maybe we can format it as one wish and one prediction.

Bethany: Okay. So I have ... Here's, here's one prediction that I have. Um, going back to the question you had of tactility and how does tactility play a, a part or, um, yeah, just how does tactility play a part in design?I think of the new raw materials that we have now in digital design. And I actually think design tokens or, in, in Figma parlance, variables are a very interesting raw material that are ubiquitous. Um, have a lot of information encoded into them and are still fairly underutilized. And so I would predict/hope that as design token usage continues to grow, we would collectively discover the qualities of that as a raw material to be working with.

Um, and then I think building off of that, as, as more of our design choices get encoded into these variables, I think that will enable more combinatorial perhaps AI-assisted prototyping, um, that ideally would be an assistant to designers using their brains and, and making choices about, um, the UIs that, that they're making, um. So I think that's a prediction/ ... I'm looking with great interest in that field as to how, how design tokens will evolve.A wish I have is that designers would just start making more weird stuff like to pull, to continue to pull from art history, from their observations of the world around them, from their own personal journeys, as we were discussing earlier. And you okay with splashing that onto the screen and figuring out how that might fit into a given flow that you're working on? For me, that's, that's perhaps a counter to working in the design system space for, or in the system space for 13 years now is that I'm always looking for inspiration, for additions to my team who have really unique perspectives, um, and can use that to shape the, the visual world and the ethos and the understandings that, uh, go into our design systems.

So ... Yeah. So I just ... I wish people would take more risks visually and with the level of critical thinking that they're trying to put into their work.

Liam: That really resonates. We, we work in user experience, but there are all kinds of experiences that people can have.

Bethany: Yes. We're not just users all the time (laughs).

Liam: Yeah. Cool. All right. Thank you again, Bethany, for joining me.

Bethany: Thank you. It was a pleasure to talk to you.