Rob Giampietro, Head of Creative at Notion and former Design Director at MoMA, returns to the show to unpack the story behind Notion Faces, the popular tool that allows users to create their own illustrated avatar.

Rob details the project's journey from a beloved internal tradition to a major public launch, including the pivotal decision to scale with human illustrators instead of AI to maintain the brand's unique, handcrafted quality.

The conversation explores how the team shifted its focus from “likeness” to “expression,” the power of modularity in design systems, and the research process that made the project a success.

Liam Spradlin: Rob, welcome back to Design Notes.

Rob Giampietro: Oh my gosh, thank you so much for having me back. It's such a treat to be a returning guest.

Liam: Listeners who have been listening for a while, since I think our 25th episode or so, will recognize you. Much of our audience might recognize you anyways. But for those who are just tuning in, tell me a little bit about who you are, what you're working on, and how you got there.

Rob: Yeah. I'm Rob Giampietro. I live in New York City. I'm a designer, I write about design, I teach design. I've been doing it for over 20 years now. I've had my own practice project projects. I've also, I've been director of design at MoMA. I Google. Liam, you and I work together, which was really fun. And then I'm currently at Notion and I'm the head of creative there.

Liam: We actually started planning this episode a few months ago after we had a chance to catch up in New York. And at the time that we met up, Notion had just launched this project Notion Faces. And we had a really cool conversation about that. So, I wanted to talk about it on the show. I think there's a lot that will be relevant to our audiences. But first, what is the Notion Faces Project?

Rob: The Notion Faces is really simply just a way for you to make faces in our Notion illustration style. And it's a tool, faces.notion.com, that anyone can go to and use for free and they can make a face that resembles themselves like a portrait. Or they can make a funny face that is just a cool piece of art, or something that helps them with a project. It sort of arose from internal traditions at Notion. So when Ivan and Simon were doing their original pitch, they didn't want to have traditional portrait photo portraits of themselves. So they hired a New Yorker illustrator, Ramon Muradov, who now is our in-house illustrator at Notion to do their portraits, in a brush and ink style, very similar to what you'd see in the New Yorker.

And those portraits also kind of ended up on the first About page on Notion's website. And then I think as Ramon started working more closely on other illustrations for Notion and people started getting hired at the company, it became kind of a tradition to get your portrait illustrated when you arrived. And then people started using those on platforms like LinkedIn or in help center situations to kind of identify themselves as what we call Notinos or Notion employees.

So that was sort of like the germ of it. But it was interesting because it was sort of a two-sided problem. As soon as we started putting out these illustrated faces, our community wanted them too. And then also, as Notion has grown so dramatically in the last few years, we, the creative team, were getting more and more and more backlogged. We had a few illustrators who had learned the style. Iris Chang is one of our wonderful other in-house illustrators. She was a student of Ramon's, and then we had a few freelancer illustrators as well. But even then, we couldn't keep up with demand. So it was almost like... It went from get it when you join, to get it on your first year anniversary kind of thing.

And then I think we also had this situation where we knew we wanted to do something that everyone in the community could use, but how to scale it and how to do it in a way, that was the question, the right way to do it at scale. But every agency we would ever work with or even get a pitch from would pitch us this idea of like, "What if you had a portrait thing that people could use?" And I think the other thing that happened was sort of over my time at Notion, we've launched a bunch of adjacent products. So we've launched Notion Calendar, and Notion Mail, and Notion Marketplace last year at Make With Notion, which was our first user conference.

And so as a user, your Notion identity now needs to be more portable across these different surfaces. Like when you send an email or when you do as calendar scheduling or when you publish a Notion template, it's actually really useful to have an identity that's portable across all those surfaces. And then, we happen to have a brand that people really love and feel connected to, and love to share their love with others about.

And so it's awesome when people want to be your hype person, and honestly change one of the most personal parts of themselves, like their face to be kind of within a style that you... Like even making your Apple emoji is a very kind of amazing thing that you want to turn yourself into a cartoon. So we just thought, "Oh, this is a great way for people that love Notion to also share that love and activate maybe new users or make people more aware of the product."

Liam: Yeah, I want to dig into that a bit. It's really fascinating that this started out as something internal. These portraits started out for people who work at Notion. And then, obviously, within the Notion community that would be a clear identifier, and maybe even prestigious to have such an avatar. But I also think a lot of companies would probably see externalizing something like that as a kind of risk that it would be so closely tied to what had been established as a brand asset. How did you all think about that?

Rob: Yeah. Well, I think one of the things that happened was because there was such a desire from our community and such a passion, that people have started making third-party versions of Notion Portraits. And so people are so passionate that they will find a way to make what they need if they don't have it or if we haven't made it yet. But when you have a group of users online and you see the variation of all of that, it doesn't really feel like a coherent community as much, but there's so much variegation in the style. And then I think illustration is just such an important part of our brand. We were really curious like, "How could we do this?" Like, "How could we give people a tool that maybe was a better quality tool than some of the third-party tools, and that made them feel more connected to each other and to Notion?"

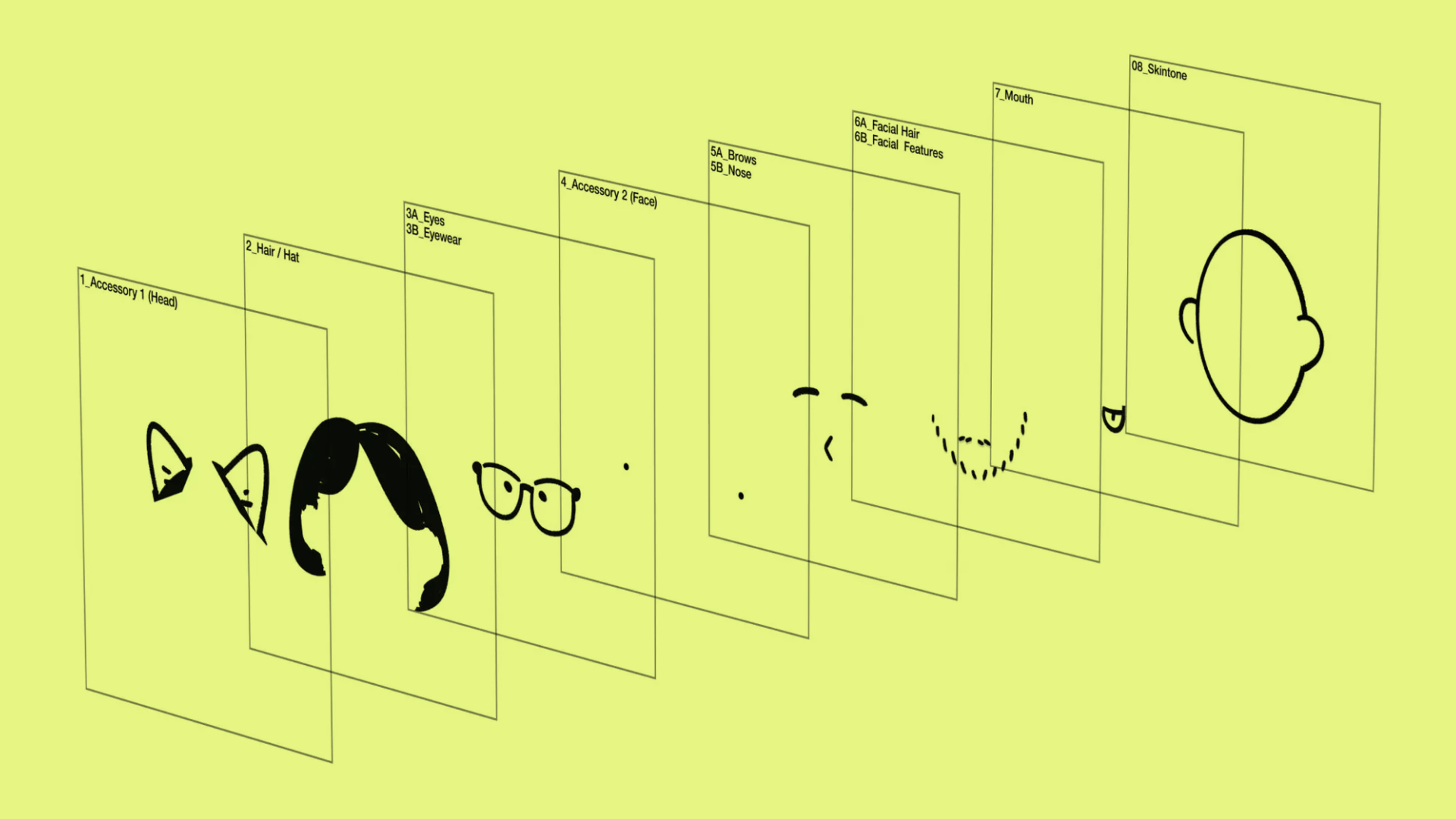

And when I first joined, I had seen there was a set of Photoshop filters that Ramon had made where you could turn on and off different layers in Photoshop, and Mr. Potato Head together. It was a proof of concept, really like a sketch. And then one of our other designers, Sam Baldwin, had taken that and moved it into Figma. So it was a little easier to use. And sometimes, we would use those for user sketches like UX sketches for marketing materials, or even back to school sometimes.

But they had a very lightweight footprint in our marketing materials. So Alex Howe, who was our lead social at the time, and David Tibbets, who's a really early Notion employee kind of teamed up and pitched, taking this Figma kind of thing, and turning it into something that we could externalize. And they just thought it would show a lot of love for the community, and create a lot of buzz and enthusiasm on social.

And so, because illustration in art direction was my department, and the baton was handed to me to say, "Okay, Rob, figure out how this can happen." And it's a wonderful... I was like, "Thank you so much. This is a wonderful challenge." But also, the more I dug into it, the more complicated I realized it was. Now I love a challenge and I love learning about a problem in that way, especially when it's pretty ambiguous. At first, we spent a little while, like the first few months thinking that the building of the tool was going to be the problem, like, "Who could build this? Could our web team build it?"

There was kind of an internal web... On a weekend, one of the web engineers had taken the Figma, and sort of tried to webify it, but it wasn't quite working the way we wanted it to yet. And then we were also wondering, "Should we try to get it on an engineering roadmap? Was that the right way?" But I think very quickly, we started to realize that the problem wasn't really engineering, it was a pretty straightforward tool that we wanted to make. The problem was actually all of the illustrations that we needed. Because Ramon had actually spent about six months in building that kind of set of Photoshop layers. And in that six month time, he'd done I think 170 or so pieces.

So the proof of it was there, but it had just been exhausting for him to just be sitting and illustrating these things and he's also doing campaigns and all kinds of other things. And we realized that to get enough to actually represent a global user base, the proof of concept was really... It looked like eight college students in different [inaudible 00:10:30]. But to get something that actually looks like the Notion community around the world, we only wanted to launch something that on day one would feel inclusive, and where people would actually want to represent themselves.

So the problem quickly shifted from being one that we thought was technical, to being one that was actually about scaling illustration bandwidth, and how to do that. And I think from there, we went onto another interesting journey because, obviously, we're in the world of generative AI right now. I think we actually worked with a company to train a model to sort of see how we could potentially take a picture that someone would upload, and turn it into a Notion face that sort of had the controls of some of the template modular stuff that we were working with. But we quickly noticed that it was very low quality.

Also, sometimes some of the dot screens and color, tints and tones that we use to represent skin color and hair color in the product, were getting really zeroed out and made white. And so, you could upload a picture of yourself, and it was really looking just for the edges or the contours of your face, rather than all of the information about your face. And so even for the initial presentation of like, "Here's what we got out of the model," we were doing some finessing and adjusting. And we realized that while it might help us with our internal employee problem, because we could do a little bit of fixing, it wouldn't scale to a self-serve product for everyone.

Liam: I want to talk about that because I think something... This project is actually a great surface to explore so many things. First of all, that you first went down the route of trying to prioritize it as an inch feature. And then ended up in what I would consider from my viewpoint, a very fortunate position of like it's not actually an inch problem. The problem is somewhere else that is maybe even, I don't know, more fun to address. But also that this is something where this scale was the thing scaling, like this art approach.

And I think especially right now, when people run into scale problems, they want to smash the big red AI button. But you all very deliberately went in the hand-drawn direction, even knowing how much work it was. And not just because the AI wasn't cutting it, but because there was really something there subjectively in the pursuit of representing humans, like you needed to bring humans into the process.

Rob: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think that was it. You're saying it better than I did. It's like we weren't getting the same kind of joy and feeling from the AI-generated faces as we were from the ones that were made of Ramon's hand-drawn components. And then I think also, while we were doing all that work, we also launched Notion AI, which is a very simplified cartoon face without a mouth actually. Because it speaks through text, it doesn't use its mouth. We call it Nosy internally. And it's sort of inspired by variously, the [inaudible 00:14:12], Tintin, Picasso, like Disney characters. It has a lot of inputs, but some Bruno Menari masks, some things, some Japanese, no masks and things. But it's the most simplified form of human face.

If you look at Scott McCloud's diagram from Understanding Comics, and there's the smiley face and then there's the hyper-realistic portrait. We actually wanted to be able to introduce faces that are not only as felt as nice as our hand-drawn portraits, but also could differentiate themselves from AI agents that might be working in your workspace alongside you. And so, there was a very intentional feeling that it needed to be a few ticks above kind of basic. It needed to be high quality, something that someone would want to opt into.

But the other thing that's interesting is that we realized that when you make a cartoon of someone, you're simplifying them. And when you have an illustrator, like doing a caricature at a county fair or something like that, they notice a lot of things that make you you, and then can heighten those things in the cartoon. And so, it's possible to use likeness in cartooning, even though there's a degree of simplification and abstraction that comes with cartooning. But the other problem we had was at scale, we don't have that sort of human intelligence working on, whether we did it through AI, or whether we did it through hand-drawn components, it was still modular.

So we needed to move away from likeness as our kind of metric of, "Is this good?" And instead, we needed to give people expression. And even within Notion, the hand-drawn portraits were starting to get hard on Slack of like, "Which brown haired colleague of mine is this?" But with expression, it's like, "Oh, Sarah always wears a party hat," because that's her silly avatar. And so, expression helps you supersede... It supersede the problems of abstraction and modularity in the illustrated portrait structure. And also brings emotion and a sense of authorship that if you as the user, instead of the cartoon artist heightening those things, you as the user are bringing confetti. Because that how you feel, and that's what you want to project at work.

So, I think that was another big unlock for us, and that was actually why we decided to call it Notion Faces instead of Notion Portraits, is that we realized that we wanted to make it possible for people to... Sure, they could create their portrait, but they could also create any face they wanted for any reason. And if they wanted to use it as a toy and just make silly faces, and send them back and forth to their friends, we wanted to make that okay.

Liam: Yeah. I think I want to pause there for a second, especially the concept of the user brings their own confetti. I think in interface broadly right now, we're seeing a move towards things that are trying to... I mean, we've been moving towards more nuanced adaptation to the user in their context for the past, I don't know, 60 years or something, maybe longer. But we're releasing a concerted effort now, especially with new technical capabilities to add that level of expression to the entire interface.

But I also want to say it's those elements both in the Faces project. But as I said, this is part of what makes this project so interesting to talk about in an interface frame. In the interface broadly, it can be those things that are not strictly necessary or that aren't directly serving a productive goal that end up making it a good experience.

Rob: Yeah, completely. I mean, I think that was a huge impetus behind the creation of Nosy, for example, the Notion AI, our Notion AI character is it didn't need to be cute face with Rive game engine animation, powering it with interpreting AI states through its facial expressions and all of that. It didn't need to do... That was not a piece that we needed to do to launch the product. But it created a really ownable and branded touch point that helps people remember that they had AI in their workspace.

A lot of times when you're trying to make a database and write a bunch of stuff, and you forget that AI is there to actually be able to help you do that. And so the delight and the kind of extraness of it is really hopefully not in any way distracting, but a really nice invitation to just remind you or jog your memory like there's an agent there that can help you.

So yeah, I think you're right. It's like sometimes it's there to just kind of keep something top of mind. Sometimes it's there because we believe, deeply, on every level of our company that people should be able to have fun at work. We have this kind of diagram that Ramon made of work and play and kind as a loop. And I think the whole idea of just almost turning yourself into your fun work self is a very Notion-y idea. It just makes collaboration a little more lighthearted and playful.

We just launched this kind of landing page where we supported the Severance podcast, and we're doing a bunch of Notion and Severance crossover things. But we made Notion Faces for the Severance cast. It's just like, once you have it, you find all of these other ways to make things fun, and make things branded that you didn't think of before. It's actually found a million uses that we didn't realize we needed it for once we had it.

Liam: I think bringing up this Nosy, the AI kind of agent of Notion keeps coming up and I think it's really interesting to think about. You said, "Of course it refers to all of these abstractions of faces." But on almost like a poetic level, I think it's interesting that it approaches the smiley face. It approaches the like you can have two dots in a line in any orientation, and recognize that it's a face. In contrast to these portraits that are much more nuanced and much more human feeling, it's almost like acknowledging that the place we are at right now with LLMs is like they are made to approach you in a way that a human does, and yet you recognize there are still clear signals that this is not a subject that you're dealing with.

Rob: Yeah. Yeah, totally. But this is a bot and not a person. And we celebrate both, that that simplified agent can be joyfully simple, and that the human can be more richly joyful and complex. And yeah, I think that's where going above and beyond to celebrate the human users of our products was precisely the message we wanted to send. We didn't want to do something that was just like, "Okay, cool. You can use our hacky internal tool." We really wanted to almost just anticipate as... We can continue to actually add parts to it as we get requests, or people... There's a feedback thing in the tool that people use all the time to say, "I wish there was an X or a Y." Or we take it really seriously and we try to create a full range of experiences in what using that part of our product means.

Liam: Yeah, let's talk about that. I want to get more specific about how you developed all of the pieces, because I think... I remember from our conversation before that it was quite an involved process that also involved many people and practitioners along the way.

Rob: Yes, it did. So let me go back to where we were in our story, which is when we realized that we had this problem of scaling illustration instead of scaling engineering, and that AI wasn't going to cut it. So then we needed to say, "Okay, how can we tackle this problem with human illustrators?" And Ramon think started to realize and be supportive of the idea that it's hard sometimes if someone's doing the whole drawing to make it look like his work, or even for him to want someone to emulate his work in that way. But when you mix pieces and they're on a grid, and they're kind of very... The style of them and the brushes and things are very dictated, you can actually have a few different illustrators. And it doesn't look bad. If anything, it's like they're creating these potential ingredients and the user is completing it.

So as we... We did some tests, and we actually... We had been working with Buck. And so they were a natural collaborator to reach out to and say they have many, many illustrators working for them. But we also wanted to have sort of selection to build a team that Roman felt really good about, and felt could work closely with him. And so we reached out to them and we said, "Here's our idea." We were like, "Cool, let's do this. Let's try to scale the illustration through multiple people rather than through AI."

But then the first question was like, "Well, how many parts do you think you're going to need? What's the scope of this project?" And we didn't actually know the answer to that question. And so thus became the next chapter of what is the MVP of Notion Faces of what... We want to be globally representative of all users, but how much is enough to get us started?

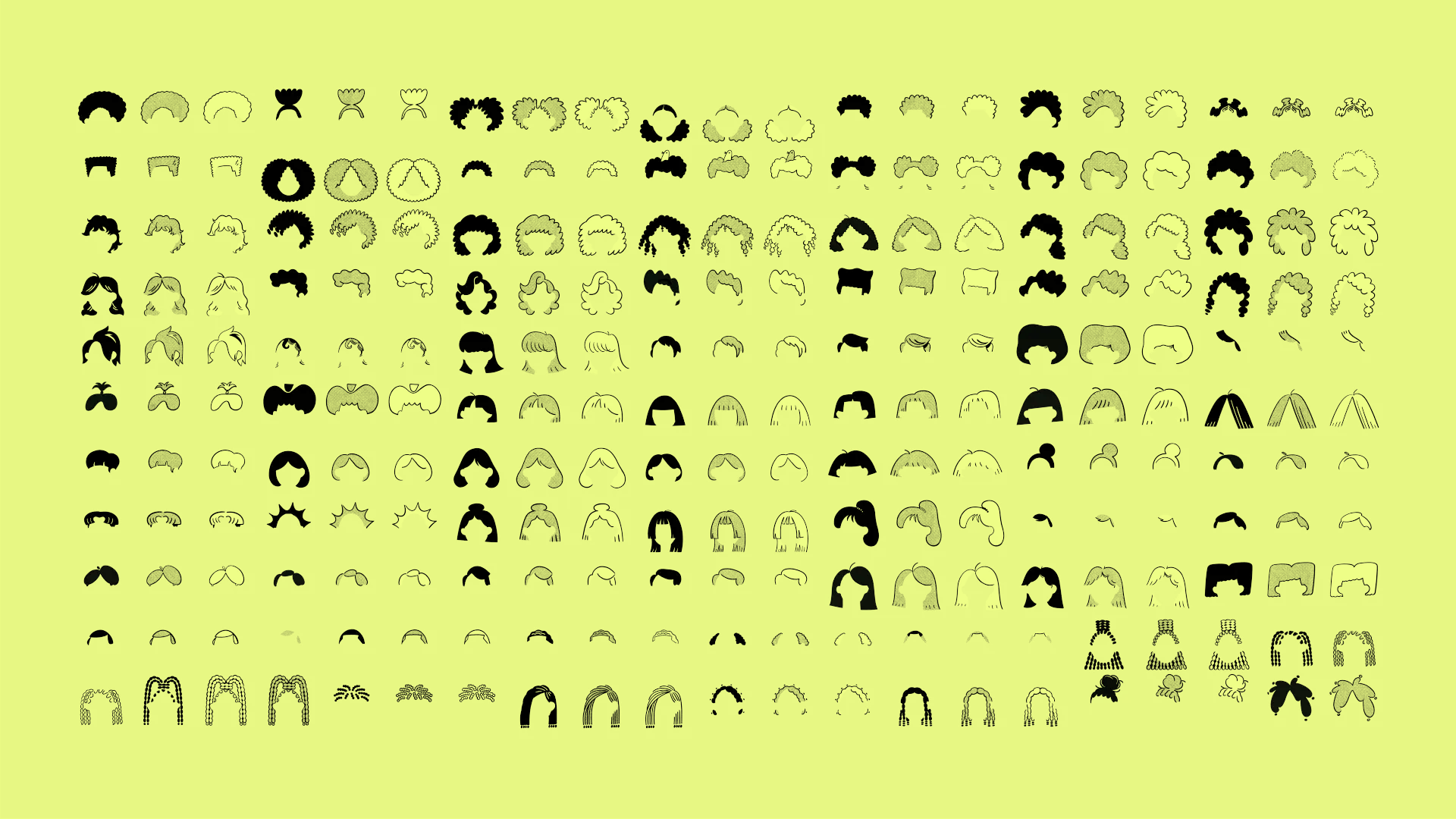

And to do that, we actually evaluated, we worked with Buck's strategy group to evaluate 11 different emoji systems that we identified with them. And look at their range of coverage from kind Memoji to Bitmoji to... I'm trying to remember all the... Lego, Lego Yourself, different things. There were a lot the interesting thing. So we learned a lot, and we got a sense of like, "Okay, we're going to need a lot of hair." That was, I think, the first big insight. And then also just accessibility was really important to us.

We wanted to be able to represent things like hearing aids. We wanted to be able to represent different types of dress that people have around the world and things like that. So I think we have roughly... I think we really tried... In terms of inclusion, we tried for roughly the coverage of Memoji, but without the animated pieces and all of the different color variations. But they have some expressive pieces, and we really did want to include 15 or so percent of the new parts to be just pure joy or pure fun, like sipping emoji, bubble tea, or whatever. That's important too. And that was sort of part of our brief, was not just representation but expression too.

Liam: How did you test this? Once you have X times X, times X number of pieces, how do you test them for coherence? Or are there certain characters that you always test? Or how do you go about proofing that? The whole system fits together?

Rob: So a couple different things. So basically, we got this list of like, "Okay, we're going to need all these different kind of hairstyles. We're going to need all these different kind of accessories, and nose, and eye styles, and different things." So we made that list. We actually then brought it in Notion. We started prioritizing it. We started putting sprints together with the illustrators. So week one delivery was going to be this set of things. We then used the internal web tool that we had built, which was still a little bit rough and ready, but we would port some of the illustrated components into that.

And then we would often test the quality of it with people that were internal users of Notion. And I think this is where maybe I should say two things, which is, number one, another interesting aspect of this project was like who should pay for it? Because it wasn't necessarily clear, it wasn't a marketing initiative alone, it wasn't a... It wound up being our wonderful ex-chief people officer Mary Ann Brown who said, "I want new Notinos to have their portrait on day one. And if I can write a check once and make that happen, that's a great check for me to write."

So she partnered... I pitched her on it, but she partnered with me to essentially help us bring Buck on to do the scaling of that work. So it's another one of those things of when you're trying to do something that kind of works at the margins of everyone's areas of ownership, you have to kind of find the right partner who's just excited, and realizes that they can make this possible, like they can be the one. So yeah, she was actually the executive sponsor of Faces, even though we then did a whole huge marketing campaign around it for New Year's.

But before that, because of her sponsorship and because of the importance of us to make sure we got this right, we would go to the different ERGs, like our black thought ERG, or Women at Notion ERG. And we would allow them to use these kinds of early components that we were making, and test, and give us feedback on how were they feeling, what were they missing, what did they not like about it.

And we got a lot of notes, a lot of feedback on... Hair was really the thing I remember the most, there was just so much feedback on hair. I still don't know if we totally have all the hairstyles that people really want, but the eyes and mouths and things are very simple. So hair is a really important part of how you express yourself in the tool. Yeah. But we worked with our own ERGs to sort of validate that. And then once we had... It was sort of like a fish food, dog food. It was kind of a rolling set of tests.

So once we finished the sprint with Buck, then we brought it to our localization team, and they started looking for like, "Okay, what will we need in these different regions that we support, and where are some questions we have about that? And then after that, before we launched in New Year's to the world, we also offered it to our internal community, kind of like trusted tester group. And so we figured as we staged it in these different phases, we would just get more and more and more feedback of what we needed to make it better. But the good news is that we did add a couple components. We did adjust some components. But for the most part, we were realizing our intent to be comprehensive was landing pretty well with everybody. So yeah, we were on track for our New Year's launch, which was cool.

Liam: Yeah, I want to talk about that, but I also want to get into two more things that came up for me while you were telling that story that map so perfectly onto the experiences of, I think, every practicing designer right now. Which are, one, getting executive support for your project is huge. I want to know about that. And two, essentially research. Especially in cases where you might not have a dedicated team for it, you were able to go to your workers basically, and ask them some questions. But yeah, it sounds like your executive support was pretty enthusiastic and might have come naturally. But were there any more steps to that process? Or how you would advise practicing designers to find that person who gets it?

Rob: I think there were folks at Notion that were excited about helping fund it if it was AI-driven, because it was really going to be showing that we can use AI with illustration in this interesting way. And I think we will find a way to tell that part of our story too. But I think for this, we just weren't... Maybe it was tech readiness or maybe it was our approach, but we just really felt like we needed the hand-drawn illustrations to get the message we wanted.

And so then once we had that, I think I was just sort of like, "Okay, this isn't a marketing campaign expense. This isn't an engineering problem." It's almost like infrastructure, you know what I mean? And it's kind of like the person feeling the pain the most right now is probably Marianne, who's our head of people ops, who's really just not getting these portraits fast enough, and is always having to apologize, and tell people that like, "The creative team works really hard and they're going to come together done as fast as they can for you. And we've just changed the policy now it's one year instead of [inaudible 00:32:20]."

And it wasn't a massive check to write. I really felt like what we spend on off sites, or other ways to make our employees feel good. In the scheme of that, this isn't so dramatic. And so I approached one of her deputies and I just said, "I'm thinking about... I'm working on this cookie project and I'm thinking about talking to Marianna about it. What do you think she would think?" And she was very approachable and we had a good relationship too, but I just kind of wanted to get a pre-flight.

And she was like, "Oh, my God, do you want me to talk to her about it? This is so cool." Because I think those teams are so often sort of working in their lane that they don't always get to do creative projects in the same way that we do. They're very creative people. But I think one of the fun things about being a creative is giving other people permission to be creative with you, and bringing them along on that journey. And so I think they were just so proud to be sponsoring it.

And then I think we started to look at what are the ways that they enable inclusion throughout Notion, and how can we use those pathways to make sure that our product's inclusive? So I was really happy when she was comfortable with us working with the ERGs, and we worked with her chief of staff to make space for that at some of the meetings that they had and everything. And it just a really powerful... It brought a lot of Notinos together. Because ultimately, this is a system that was designed to represent them. So it was really cool.

Liam: I do also want to get just briefly into the aspect of time. Because I think if we think about this as a user experience, I think the time that it launched, which as you said was coinciding with New Year is pretty significant in terms of how people experience this. And also what people's first experience with Notion might be because of this.

Rob: Yeah. So once we had basically the tool, and the pieces all made, and it was working really well, we did that over the summer and into the fall. And then, we had this initiative to do some top of funnel growth for Notion. And New Year's is always a time where people are signing up for Notion, they have projects they want to do, they want to change the tools they're using and use better tools.

And so we just realized it's always been a quarter for us, it's been very important. And it's a great time to bring on new users who are trying to do something that their other tools maybe aren't allowing them to do. And so we kind of had this very simple idea of New Year, new you. And we realized this is... The new you could be Notion Faces. And then it became really interesting because suddenly, top of funnel, growth dollars and things started moving in the direction of launching Notion Faces.

So it was sort of like a product launch or feature launch, but that happened to be a growth campaign also. And so I think people just were inspired by the quality and the vision of the product and they started... This is also very true at Google when I was working on Google material, it's sort of like how a bill becomes to law, and you get people to start co-signing, and sponsoring, and bringing it forward up the different levels.

So yeah, it's creating that sense of partnership. So Andrew [inaudible 00:35:42] who is our head of growth marketing really helped move a lot of dollars in the direction of the campaign so that we could hit that New Year's moment, which happened to be kind of in our Q4. So it was also great because we were just like, "You know what? Let's just make this big, and let's really celebrate finally giving the community this thing that they really want."

But we also tried to do it in a smart way, so we targeted LinkedIn as our primary surface. Because we want Notion to be something that people use at work. And we thought that that platform, it has a very normal vibe. And we just thought this would cut through, and be something that really would catch people's attention, and that they could participate in. They could change their LinkedIn profile and give...

Even if they weren't Notion users, they could just enjoy the tool to have fun that week on LinkedIn. Or just bring a little bit of pizzazz to their profile. So we work with Corporate Natalie a little bit who's an influencer. And we also, for this campaign, partnered with Snoop Dogg, who is obviously an icon and an incredible musician, but also someone who does a lot of work with small businesses and is an incredible influencer on LinkedIn himself.

And we really felt like all the work we had done to create this much broader set of components, it makes people like Snoop Dogg be able to make their avatar be really what it looks like Snoop Dogg, you know what I mean? It really looks like him. Really looks like Adam Scott from Severance. And so I think that was also a really fun thing to kind of partner with him and his team to be like, "Here you go. This is the thing we made for Snoop." And like, "Does he like it and does he want to talk about it?"

And that just really... It was sort of everybody's a little sleepy from the holidays and coming back, and checking in at work. And then suddenly Snoop's like, "Look at this cool thing I made." And everybody is like, "I want to make that too." It became this sort of amazing viral LinkedIn hit. I don't know if it surprised us, because we definitely were hoping that would happen. But it definitely... We were so excited and inspired by what everybody did with it and how they embraced it. And it was over 90% positive sentiment. I mean, we really heard very little kind of concern. It was more just more and more. So that's why we did this fast follow Valentine's Day campaign with some hearts and other things, red components and things like that.

Liam: Nice. Rob, I want to wrap up our conversation by asking... I've been asking people lately... I stopped asking about the future. Now there's kind of enough future happening at the moment. I want to know what you think is kind of the most urgent thing for designers to focus on in their practice right now.

Rob: Really good question. It's cliche, but I think we're all adapting to AI. We're all trying to figure out how to embrace that and use it in the best possible ways. And I've always been of the mind that once it becomes a feature with a name, it stops being AI and it just becomes a normal feature. So autocorrect at Google is a great example of... It's pattern recognition, and it's pattern completion, and it's AI. But we don't call it AI, we call it autocorrect or autocomplete.

And I think there's so many AI tools that are kind of going to, within creative work, especially I think that are going to go on that same arc. And I think it's about, as a designer, learning those new tools, staying fresh in your discipline and all of that. But I also think maybe the other piece that goes with that that's interesting to think about is, and I think materials always doing a great job thinking about this, is around expression.

And those tools allow you to create things that are so different from things that you maybe would've made yourself. And where does that kind of expressive capacity go? Does it benefit the user or do we stay within really rigid and highly defined systems? People want expression, they want interfaces that aren't boring. They look at this all day long. We always talk about having the product feel like water and feel like it's a neutral surface that you can create, bring the components and pieces, and put them together in the way that you want.

And I think that winds up making it very expressive, even though it's very neutral. But I think also when you're doing that kind of deep analytical work in your brain, having less complexity, it's helpful when you're hailing a cab or buying food to bring to your house, a little bit of joy and celebration and expression probably makes that moment a lot more fun.

Liam: Sure. Yeah. And bringing it back, it's those bits, those aesthetic pieces that feel unnecessary. I think part of what we're responding to in design is the over-optimization of the interface. There were articles five years ago about how everything is a white rectangle with black sans serif text now, and we're looking for those pieces that aren't strictly necessary, but add some feelings, some sensory experience to the whole thing.

Rob: Yeah. And I think that the companies and apps and brands that embrace that are going to be brands that users pay attention to and remember. And I think there's a sobriety to the previous era of design that was very cautious. I mean, it was very tasteful, but it was very cautious. And I think now we're trying to have more fun, and maybe take more risks. And let users decide a little bit when it doesn't feel like the right risk or going too far.

But you need a lot of belief from a leadership level in design and in the power of design to be transformative and iconic in order to ship those types of interfaces. And I think it's cool to see that that's starting to happen, and that like... There's just some great like, "It's pink. Oh, my God." There's just stuff where you're like, "That's risky or that would've been risky at a certain point in our design culture, and it's not anymore." And I love that we've made space for that.

Liam: Absolutely. Rob, thank you so much for joining me again on Design Notes. This was great.

Rob: Oh, it's been a pleasure. Thank you for having me back. I hope I can be like a five timer or something like-

Liam: Yeah, absolutely.

Rob: I'll have to keep making cool projects, so I'll try to keep it up.

Liam: All right.

Rob: Thank you, Liam.