When I lived in New York, there was an old bookstore in my neighborhood. And when I say “old bookstore,” I mean the store sold old books.

I first discovered the shop when I enrolled in an introductory course in Type Design at the Cooper Union and my teacher had advised us to find a few very old books to try reviving their typefaces.

One afternoon in February 2020, I stopped in to take a look around. I was by then already doomscrolling about a spreading virus, so it was a nice reliable distraction to have a look through some old books. I ended up finding two identical books—copies of T.S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion from 1939.

The pages were full of sketches, scribbles, and other marginalia from actors who had played in an NYC production of the play.

One copy had belonged to Sylvia Short, who played Mary in the Phoenix Theater’s 1958 production of The Family Reunion. Some of her notes read:

Am I for or against [the] idea I'm saying?

Do I like or dislike what I'm saying?

Am I talking to anybody or to myself?

Am I like the person I'm talking to?

Elsewhere, there are notes, provocations, or reminders on individual lines of the script.

“Oh, you don’t understand!” Mary says. Sylvia thinks, I haven’t made it clear. In this line, Sylvia notes, Mary is “talking to [her]self.” The line doesn’t just convey that Agatha literally doesn’t understand, but that Mary thinks she may have had a part to play in that lack of understanding.

Sylvia Short appeared in this play relatively early in her career, going on to perform in Newsies, The Birdcage, and I Still Know What You Did Last Summer.

The other copy of the script belonged to Fritz Weaver, playing Harry, also relatively early in his own career, having had his Broadway debut just a few years earlier in 1955.

Inside the book, Fritz’s notes fill the margins. There are also technical notes on delivery, like inflection or intonation marks on certain lines and words.

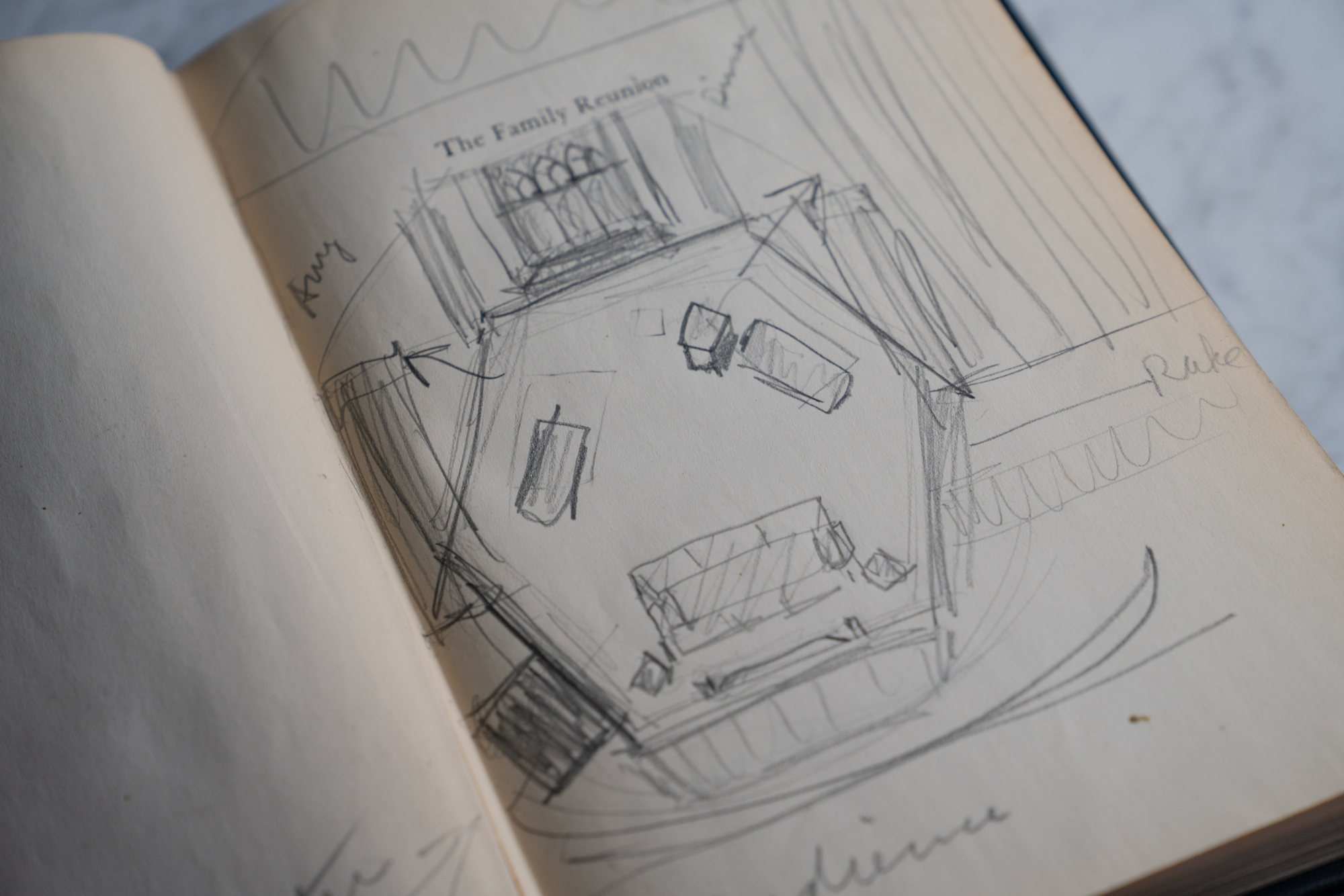

On the title page, we can even see a sketch that gives us a look into the staging of the Phoenix Theater—an exciting glimpse of a space that no longer exists. Weaver drew the stage and furniture, giving an idea of how the show might have been blocked out.

Weaver would also go on to have a prolific career appearing in plays and numerous TV shows like Matlock, All My Children, The Love Boat, and Murder She Wrote.

But the story doesn’t end there. Fritz and Sylvia were actually married to one another at the time of the 1958 Family Reunion performance. They played Harry and Mary, two characters who—despite Harry’s mother’s imaginations—don’t end up becoming involved with one another. In real life, the pair married in 1953, five years before the appeared together on stage. They would stay married until 1979. Sylvia would go on to move to Santa Barbara, while Fritz ostensibly stayed in New York, remarrying in 1997 to actress Rochelle Oliver.

I went to the bookstore that day looking for a distraction, maybe some design inspiration. I ended up discovering two award-winning actors and a rare look at how they approached their work early in their careers.

There’s so much context recorded in these books, in a real, tangible way that shows not only a glimpse into their lives, but a record of how they approached their creative work and how they interacted with the material at the time.

This post isn’t strictly related to design, but I do think there’s something to be said for the preservation of this sort of interaction, ideas, and execution.