How many times have you seen an image that describes the experience of a UX designer?

The image that has probably been the most pervasive, vacillating between ironic and earnest at various moments, is that of two bottles of ketchup. On the left, there’s a glass bottle that stands upright with a metal screw top lid. The kind of bottle you have to hit with an open palm or stick a knife in to “get things going.” But, the image implies, it’s aesthetically nice. It stands for the type of design that looks nice, regardless of its impact on our experience - there is an implicit value statement in the image that this bottle, helpfully labeled “UI” is mostly concerned with visuals and sacrifices all else.

On the right, a plastic bottle with the lid facing down. This one squirts, and gravity helps the ketchup stay near the opening. The lid is even bigger for better balance. It is, ostensibly – given the label “UX” – a bottle whose primary concern is ease of use, a good experience, and more ketchup. The image of course can’t illustrate that this bottle you still need to shake beforehand, will probably fall over at some point, gets crusty around the opening, and is made of single-use plastic that is, in all likelihood, going to be dumped in the ocean.

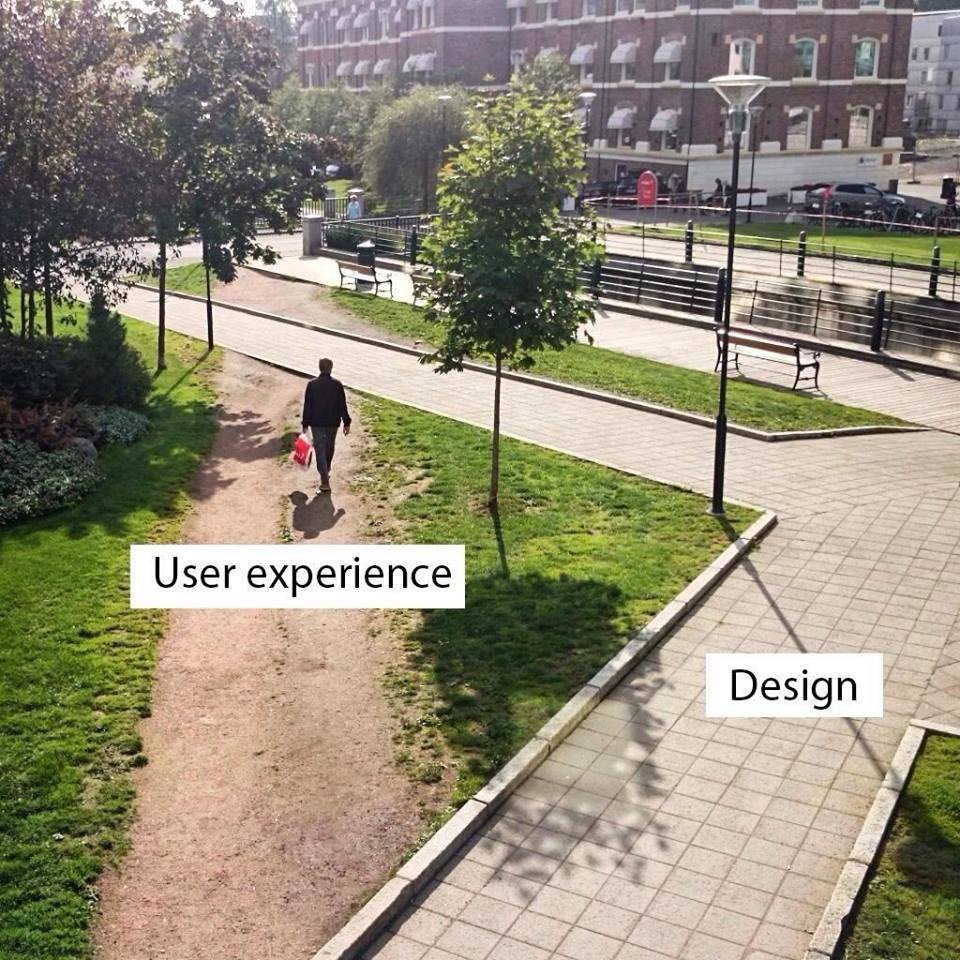

Then there’s the “desire path” image, showing a well-trod dirt path cutting through grass next to a perfectly maintained sidewalk. The sidewalk is instructively labeled “design,” again aesthetic, full of visual function and meaning, clearly representing a design intent, and the desire path is labeled “User Experience.” This image, too, is loaded with implicit beliefs. The desire path would tell us that perhaps a designer should have made a diagonal sidewalk instead of a perpendicular one, or perhaps that user experience really means that the user will do whatever they want to accomplish a task, no matter how carefully we’ve placed our bricks on the path.

Finally, though I’m sure this isn’t the last image that comes to mind, there’s the gif of a guy with a glass of water who can’t seem to take a drink¹ - a straightforward task like drinking water is made to look impossible even though to us, as viewers, the answer is right there. If we’re viewing as designers, we see that someone has designed a glass for holding water and putting it to your mouth, and we give a knowing chuckle to the representation of a user who just can’t figure it out.

These images feel relatable to us at different stages of the design process, and can provide some much needed comic relief, but they share another common factor with one another: they frame the intent and context of the user as an aberration, something to be worked around, to predict and influence, to standardize or, in the worst case, to ignore.

If these images are any kind of touchstones for our understanding of our discipline, we can probably use them for some critical reflection, too. Our work creating interfaces doesn’t typically deal with ketchup bottles, sidewalks, or glasses of water. The technology we use to implement an interface is digital. The metaphorical ketchup bottle we’re producing doesn’t even have to have a fixed shape – ours is customizable. Its shape, color, size, elevation, placement, are all easily changeable. Likewise our sidewalks can be reconfigured for specific use-cases or tasks. A trail through nearby grass shouldn’t be a problem or an interesting side-effect, it should be something we welcome and facilitate. Why can’t someone drink out of the bottom of a glass of water, when the glass itself is virtual?

If we imagine this happening in actual space it sounds a little outlandish. We understand these objects to be the fixed result of a process of production. Even the word “product,” which we certainly use to describe our work as designers and developers, implies something that is produced, something lying at the end of a process rather than in the middle or the beginning or somewhere totally outside a process of creation as we would currently conceive it. As such, most products are resistant to change. They’re inflexible; their properties are unbending; put simply, they can’t adapt.

Mass Production

Many if not most products we encounter today are also understood to be the result of mass production, a process that owes its speed and efficiency to the standardization of the objects it produces. To make a new type of ketchup bottle, you need new molds for glass or plastic, new designs, machined parts that can precisely reproduce the bottle over and over again. Over time, incremental improvements are made in response to material costs, manufacturing processes, customer response, and aesthetic trends. That is to say, all products are the outcome of a conversation between a creator and a person experiencing the creation. But most people will be using the same ketchup bottle for a long time before a new one comes along.

With the advent of digital or virtual products – that is products that are reproduced with low-level materials like electricity rather than higher level physical materials like glass or concrete – the pace of this conversation has quickened significantly, and has the ability to become more dimensional and inclusive than before. As people making products for a digital platform, we have an unprecedented ability to iterate on ideas and change products over and over again, fine-tuning them to match our goals and the goals of our users. Despite this, we are still essentially manufacturing new ketchup bottles really really really fast, rather than changing something in the fundamental discipline of I guess, in this metaphor, containing and dispensing ketchup; something that would provide the basic capability of dispensing ketchup, but leave the details – grip, volume, weight, shape, color – up to each person’s own realities. Keller Easterling, in a discussion of her book, Extrastatecraft put it best:

“You don’t square up to every weed in this field with a righteous fight; you change something in the soil.” ²

Our collective gaze in designing digital products is fixed on systems, standardization, and the notion of “best practices” to solve problems. We have a set of tools that we continually apply to what is, fundamentally, an immeasurably nuanced set of questions and needs. When we finish using the tools, we distribute linear updates. In other words, we, too, practice mass production, and address each weed in the field with incremental improvements. In actual application of our practice, it isn’t the conversation that’s gotten faster – it’s just the distribution.

And as we push more updates, we create more products. And these responses to the externalities I mentioned before can only happen in aggregate because we are only shipping one app or product at a time. An aggregate approach means that, in all likelihood, no one thing is designed specifically for any one person.

On the other side of things, as people called “users,” we find ourselves trying to find and fit into workflows, developing new intentions in order to satisfy our existing ones by “learning” to use interfaces, keeping up with abstract patterns like navigation or gesture controls. This experience is especially acute for people who haven’t been included in the evolution of interface design, or who might be encountering these kinds of interfaces for the first time.

As a response to this, in 2015 and 2016 when I began working on Project Phoebe, which was my first foray into imagining other futures for our discipline, I discussed the need for digital interfaces to make themselves prolific, becoming what each person needs rather than what an aggregate of many people may need.

I want to revise that approach by adding that interfaces should be based not only on individual needs but also intentions - those that are, crucially, not the ones established by designers. Interfaces should follow rather than shape the needs and intentions of the user. The process of moving toward this goal will fundamentally transform our approach to designing interfaces.

The shifting role of design

But let’s catch our breath and consider how we talk about our work for a moment. For the designers reading this, some of us may consider ourselves to be “product designers,” the creators of products which, as we discussed, lie at the end of a process. We “design” the results of that process, crafting a path to reach them and a product that can, ultimately, reproduce that path for other people. Some of us prefer the term “UX designer,” and we are the creators of something that is experienced by users, or experienced through use. We can also be “UI designers,” who build the substrate interface upon which the product can reproduce its results. Still others are “interaction designers,” and we say that we are “creating” interactions that people can execute with our digital objects, invisibly guiding their eyes, hands, and thoughts as an architect might conceive of guiding a body through space. Within and without these categories there are numerous other specializations and generalizations, but the semantics of our titles are not important.

In all these scenarios, we are operating with a mentality shaped by the received knowledge of our industry, which is itself shaped by the received knowledge of the capitalist organization of our economies. The mentality is one that relies on the idea, mentioned earlier, that user intent is something that needs to be predicted, documented, worked around and, most insidiously, influenced by the product makers; it’s an approach that sees consumption - rather than creation - as a primary mode of experiencing the world, and this is starkly reflected in our work.

To begin to break our discipline out of this rut, consider what it might be like if the people who we now call “users,” were instead “creators.” If the people who are now expected to passively experience and consume a product, dutifully reproducing results designed by our intention, actually could derive their own experiences by expressing their intention. How radically different could our work, as designers of all types, be?

Let’s explore that.

What is “interface?”

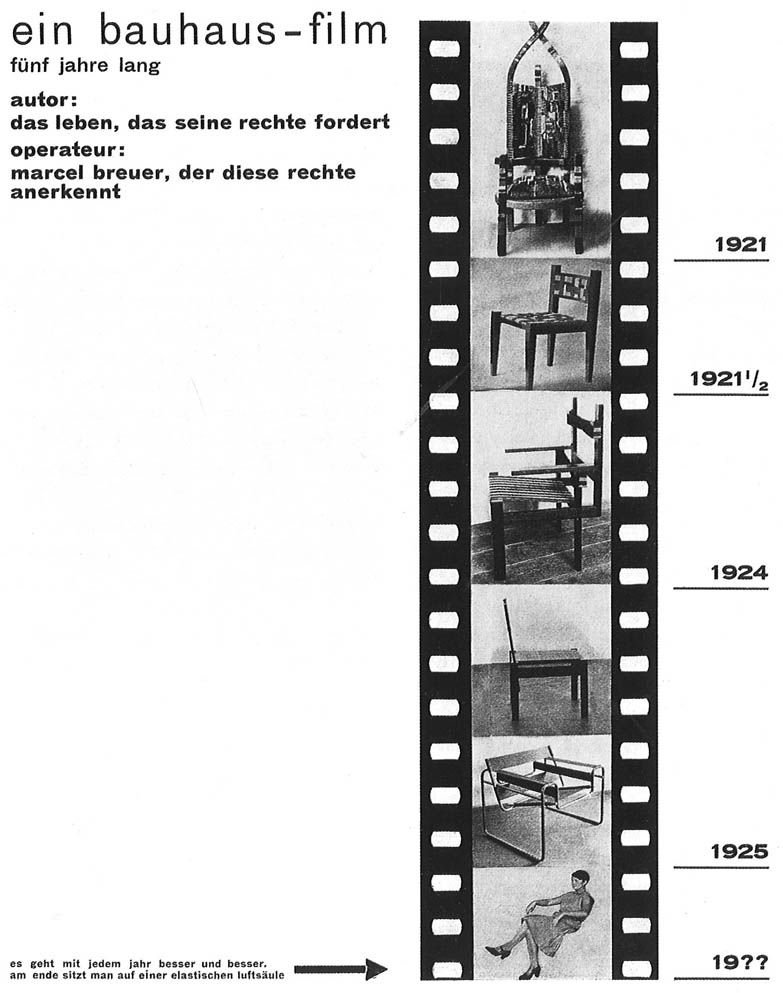

In a SPAN 2015 session called The Interface³, architectural historian John Harwood discussed the history of chair design as a means of understanding the object/subject relationship between people and the objects that govern our experiences of the world. The talk began with Marcel Breuer, a modernist architect with a prolific portfolio of furniture produced during his time at the Bauhaus.

Breuer understood the peculiarity of the dynamic between creator and experiencer, illustrating in a 1926 poster⁴ that “[chair design] gets better and better every year. In the end, one sits on an elastic air column.” The humor of imagining that what we consider a “chair” will be transformed into something that is indeed so elastic that it no longer physically exists must stand side-by-side with the lived experience of all chair-sitters that actually, chairs are often not that comfortable, and that one chair has difficulty supporting multiple needs.

Photos by @whoishaleylawrence, @xcrap, and @sweetspotphoto on Unsplash

Even if it’s great for one purpose like seating many people at an event, or fitting into a corner, or looking great on the patio, it might not support you after a long hike, or hold you and your child as you read a book together, or survive bad weather. An invisible, elastic air column really doesn’t sound so bad.

This example underscores that the concept of “interface,” as a description of the dance between subject and object – between human and technology – has been floating around for a long time. The chair was understood by Breuer and others to be one interface – something nominally, if not practically, designed with a human in mind, but ultimately, as a static object, exerting its own object will on the person who ends up sitting in it.

Photos by @fesh00, @octadan, and @charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Architecture, the tangible outcome of which is itself interface, already recognizes the potential here, edging physical products toward a malleable, dynamic mode of experience through movable elements like shoji panels, curtain walls, and other components that allow occupants to easily reconfigure physical space in a way that a chair usually cannot.

We know, as creators of digital environments, that we have an exponentially larger capacity for expressing this type of potential in our own work. An interface in actual space – as opposed to digital or virtual – could be the physical contact between a body and a chair, while ours is often finger-, voice-, eye-, and ear-to-device. Consider that a chair rarely learns anything from how a person sits, or where they want to put their feet, or what they can do with their hands.

Footage from The Fabricant

Designing for Self-Actualization

Kerry Murphy is co-founder of the Fabricant, a studio that produces virtual couture; that is, clothing that exists only in virtual space. When designing garments for virtual space, Murphy says that his studio uses the “language” of physical clothing design, while materials are unbound by normal physical constraints. The “raw materials,” he says, are data. The texture, strength, color, weight, and dimensions of fabric are expressed as ones and zeros. In our discussion on Design Notes⁵ Murphy also divulged his experiences creating and manipulating a photo-realistic virtual avatar of himself. Through trying on challenging garments and programming his body to perform heretofor impossible movements, Murphy uncovered something about the self-actualizing potential of digital or virtual experiences.

“My first reaction was like- like, ‘No, I would never wear that,’ but my second reaction was like, ‘But hey, what if? … How would I feel if I would go out into the open with this weird clothing that I'm wearing in my digital life?’ All of the sudden, I started becoming much more open to things that I was not necessarily open to before.”

This embodiment allowed him – as it allows others – to reflect on what it would be like if their actual-world intentions could be easily satisfied. More than that, it drew into question the subject/object relationship that Breuer and others would have assumed before the advent of sophisticated digital interface. Suddenly, the object will of the images being presented to Murphy was actually aligned with his will as a subject; directly shaped by it, in fact. The conversation became two-sided, and both were in agreement.

Tom Boellstorff echoes this dynamic in his ethnographic work on virtual worlds, including his 2015 book, Coming of Age in Second Life⁶, noting that, “corporations who simply saw Second Life as ‘interactive’ misrecognized interactivity for creation: the cultural logic in play was not that residents interacted with a commodity and its producer, but that they literally produced what they consumed through self-actualizing acts of creation.” The implications for virtual worlds – where residents can create their own body, clothing, house, and decorations using data as raw material – are clear: the resident of the virtual world exists as an entity solely through their own acts of creation within that world. Their intention for their own presentation and integration into the social milieu of virtual space is directly manifested through the world itself and the interface that governs life in virtual space.

Zooming back into our own work from here, (work which largely manifests itself on screens in the actual world) we can begin to get a better understanding of the work’s self-actualizing potential, and what it may look like to give individuals the power to create their own experiences with our products.

In the same text, Boellstorff asserts that intentional creation is not the only type of creation we have to consider when studying how intent and identity manifest in design. Besides intentional, explicitly planned creation, emergent or situational creation plays an equally important role in an individual’s virtual presence and actions. This Boellstorff compares to Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s distinction between grammar and speech – the planned logic and mechanics of language against the practical application in everyday life. Boellstorff notes that the concept of design itself “presumes intentionality” on the part of the designer, a possible “misunderstanding of the present” that hinders our ability to imagine the future, a future, by the way, that Boellstorff admits – as we all must – is ultimately unknowable.

If we want to transform the discipline of design, then, by giving it a new foundation – one that doesn’t entirely rest on our intentionality as designers – we have our work cut out for us.

Information + Action

Right now, the digital interfaces we find on personal devices can be boiled down to two primitives. These two primitives, which I’ll call information and action are the building blocks of what we would now call user experience. From these primitives, we derive components. Components come together into UI regions, UI regions comprise screens, and screens comprise flows, and flows comprise apps. You’ve almost certainly seen it broken down like this before, from small abstracted concepts to large practical applications – I would consider all such models valid propositions, with the note that information and action are the smallest particles we can observe directly.

A foundational constraint that we often acknowledge and account for in design is “human factors,” or the realities of the human body and cognition that impact how people are able to interact with an object. These principles, which have been variously documented by standards bodies⁷ and design practitioners (myself included), often appear at the bottom of a layer cake of considerations in discussions of interface design, but in a model organized from the principles of information and action, human factors are more like the shape of the cake itself. In the future presented here, individual intent would be a human factor that – just like touch, voice, vision, hearing, and cognition – we must be able to account for in the things we create, without precise knowledge of what it is or how it might change.

In other words: if information and action are the primitives that grow, seedlike, into the full flower of an interface, how people choose – and are able – to interact with technology at that interface is a superseding layer, and that is where true adaptation really lives.

✧

Bringing Interface into Design Space

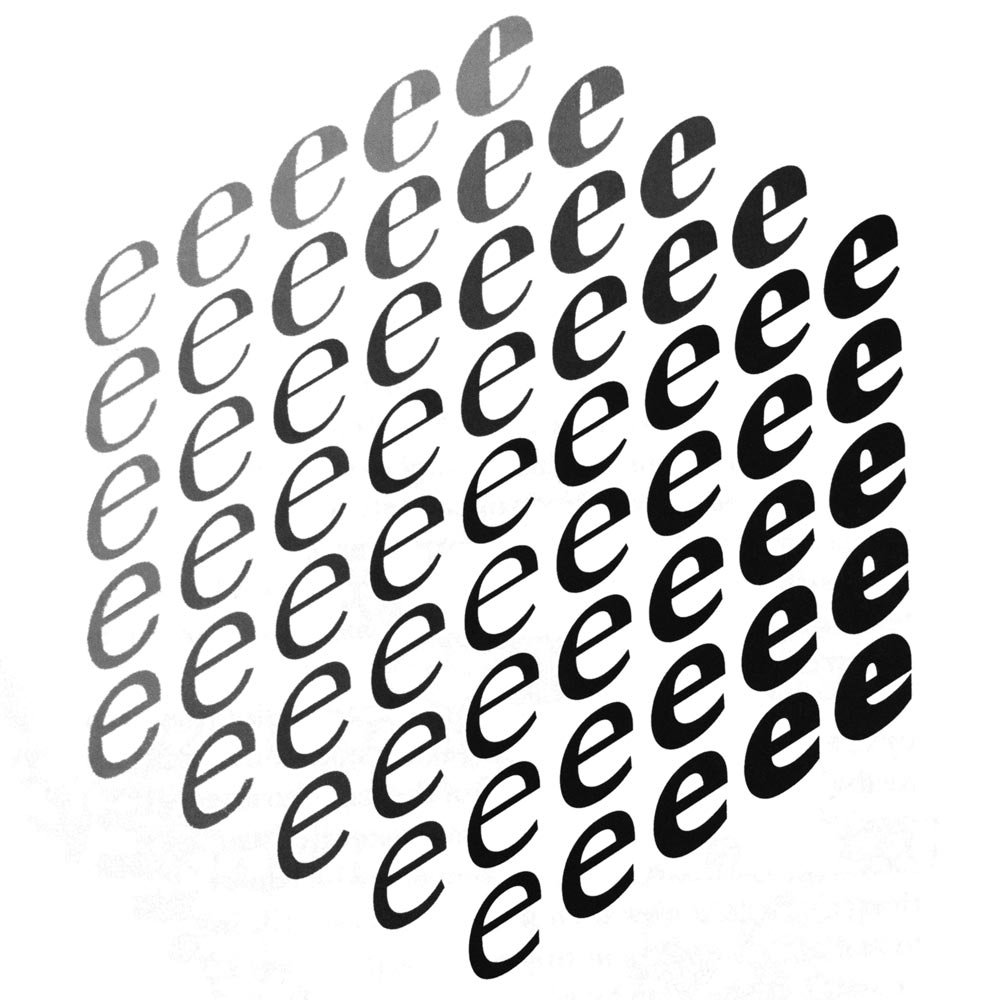

One successful implementation of design based on this type of intentionality is the accelerating development of variable type technologies, fonts that are not packaged as individual styles as foundries have for hundreds of years now, but rather as one program that constitutes a continuum of possible expressions of a typeface. The product of the design process for a variable typeface does not presume to know or understand the intent of the creators who will work with it later – graphic designers and typographers are constrained only by which variables (axes) are made available within the typeface.

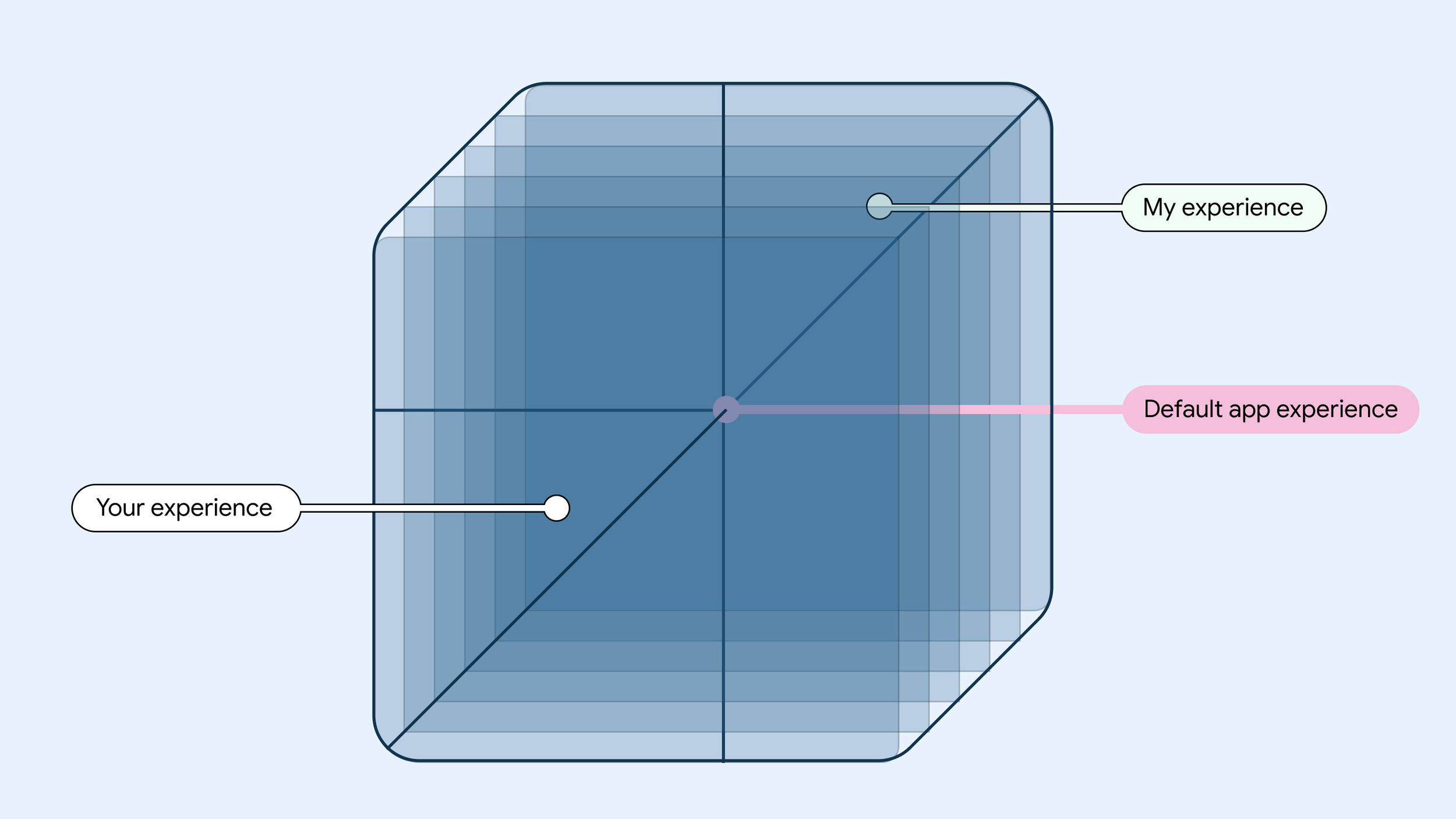

When I studied in the Type @ Cooper program in New York, I learned from type designer Hannes Famira that a “font,” the instance of the typeface we were designing in class, was just once point in a multi-dimensional field called the “design space.” The variables in variable type, called “axes,” run through this design space like overlapping train tracks. Anywhere there’s an axis, we can see a continual line of expression through the design space. Some axes, like “weight,” run straightforwardly from one point to another – for example from thin to extrabold. Others intersect one another, drawing themselves into two dimensions. Others go on to become more complex, even having influences on several other axes as they progress through their own scale.

Project Phoebe saw digital interfaces as existing within their own kind of design space, where axes like touch or visual acuity, age, and others could all influence the instance of the interface a person is presented with. And today, we actually do have a few ways of instantiating somewhat complex axes in our work.

The Near-term Approach

A simple example to start with is adaptation across screens. In Material Design, we’ve created guidance for adapting to screens from large to small. The screens or breakpoints we document could be understood to represent individual stops on one axis – screen size – running through the design space.

But if we look more closely, it becomes easier to see moments where other axes may be running parallel nearby, or intersecting with screen size in interesting ways that we must account for. For example, on a very large or small screen, we can make certain assumptions about the device to which it belongs. A screen that’s TV-size might actually be a TV. This is information we have access to when creating an interface. What, then, might be the other axes lying just to the left or right, or overlapping with its screen size?

Design guidance for TVs specifically draws focus to things like attentiveness. We can draw from research and experience a rough knowledge of how attentive one is when watching TV and create an interface that matches that attention with the right level of detail, size of components, and types of information.

The way we organize actions around that information could comprise another axis having to do with input modality. On a TV, you’re likely using a remote control, gamepad, or other input device, rather than directly making contact with the screen. These possible modalities represent stops along this other axis, and this axis will inform how the interface is ordered in your app – how quick is it to traverse from one item to the next, or to reach a desired item from the top of the screen?

The natural direction of this line of thinking is to fully realize these and other axes for each app – and, eventually, an entire system – in a multidimensional design space, allowing an interface to function as one piece of technology that contains within it a fuller range of possible expressions, directly informed by individual intention; the person using the interface could determine where they land in the design space through their preferences, actions, usage, and implicit cues.

Material You, introduced in Android 12, is one small step in this direction, opening up the system to an unknowable form of intent (user-selected wallpaper) which it uses to inform fundamental qualities of the interface (color schemes). In this case, the axis of color expression is populated by the HCT color space, which was created specifically for accommodating unknown user intent with perceptually consistent responses.

There is, of course, much more work to be done if we want to realize a fully adaptive future at a system level, whether we’re talking about a design system or an operating system. (And I think we have to talk about both.)

Designing for Intent

In the more distant future, I believe that the interfaces we encounter on personal devices will be much closer to a pure flow of information and action rather than being deliberately and carefully grown from primitives to entire flows and apps.

The interface will likely exist in a framework that allows it to spontaneously arise and conform itself to emergent patterns based on the intent and subjectivity of the person using the device. The interface is, in this model, still the site of our encounter with technology. But the dynamic between object and subject (the chair designed for humans having material impacts on the humans that use it, the virtual couture designer encountering himself in virtual space) will shift, and we will see our own intent directly shaping the interface with which we’re presented.

This future would realize the promise of unwinding the designer’s intentions for the user – their behavior, their actions, their outcomes – and reconfigure the relationship, transforming it into one where the intention of digital production is simply to fit into the human environment seamlessly. The problem is no longer how to engage the user in an app, it’s how to unlock a specific possibility to the people who want or need it, using information and action.

Project Phoebe described an intermediate adaptive model that augmented existing approaches to create something responsive to invisible cues. A lack of touch acuity, for example, could be detected by nesting touch targets around a button; this was an existing technical implementation augmented for an existing component to become more than what it is.

Under a model whose interface is comprised solely (or at least mostly) of action and information, the design space discussed before could keep its axes while the visual and spacial presentation of actions and information becomes simpler and more modular.

New Deliverables

Our focus as designers, then, would be less on designing screens, flows or features, instead shifting toward meeting intents through organic composition. Our job as designers would then be to ensure that actions are presented according to information that matches the intent of the person using the interface.

We would find ourselves establishing anchor points within a multidimensional design space, determining the basic variables and boundaries that would ensure smooth gradation between regions of the design space which, in more concrete terms, would result in interfaces that remain familiar and usable and preserve the user’s mental model, but which adapt in similar ways to those described in Project Phoebe: individual actions that we might now call components would shift, adapt, and reconfigure themselves within a dynamically orchestrated layout, capable of composing and recomposing itself both in immediate response to state-changes and in longer-term progressive changes.

Design’s Responsibility

By this point it’s clear that changing the way we understand and practice our discipline will be complex. It will rely on new technology, experimental thinking, expanded resources, new tools, and a theory of design practice that reckons with our own position in the world as designers and the influence we have on how the world is experienced. In an interview for Design Notes, Senior UX Design Manager and former MoMA Design Director Rob Giampietro underscored the gravity of our work that I think makes this new model imperative:

It’s such a privilege to get to make the interface for the world. You’re deciding when someone should turn the page, how heavy their phone is that they pick up every day, whether they need to swipe to get more information or can have it right on the screen. All of those things are ways that you’re actually changing someone’s experience of their life through design. And I don’t think there could be a more transformative discipline than that.⁸

“Transformative” is an apt word here: When we design something, implement it, and put it into the world, we are causing transformation. At the surface level, we’re transforming someone’s experience of their life - that’s big enough. But we’re also transforming, potentially constraining, the range of possible experiences in the world by making choices about what a product can do and how it can do it. And we’re transforming ourselves; our discipline often puts us - our perspectives, our experiences, our beliefs - into the world within the products we create, just by virtue of the fact that we are humans creating things for other humans.

In other words, we are unavoidably present in our work. That goes for anyone who creates anything. The lives we have led until the point that we make an intentional creative choice will inform the outcome of that choice, no matter how hard we resist. This makes design a political and social action, and places a large amount of abstract – and, often enough in our industry, tangible – capital in the hands of relatively few people.

The only way to unwind some of the power we have assumed as designers is to build a process that deliberately dismantles it, putting the people we now call “users” in a better position to make their own choices, build their own experiences, work toward their own intrinsic incentives; a process that allows us to give up the notion that those things ever belonged to us to begin with.

1 “‘Gravity Falls’ Boyz Crazy.” IMDb, IMDb.com, 19 Apr. 2013, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2813658/.

(It’s worth considering that this gif was clipped from an episode of the show Gravity Falls in which the men pictured are revealed to be imprisoned clones.)

2 “Keynote: Keller Easterling and Geoff Manaugh in Conversation (Span NYC 2015).” Google Design, YouTube, 6 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBdJSLSS550.

3 “TALK: The Interface (SPAN NYC 2015).” Google Design, YouTube, 6 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wa7c_LrsWbo.

4 Barry Bergdoll. Marcel Breuer Bauhaus Tradition, Brutalist Invention, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, 2016, http://resources.metmuseum.org/resources/metpublications/pdf/Marcel_Breuer_Bauhaus_Tradition_Brutalist_Invention.pdf.

5 Spradlin, Liam, and Kerry Murphy. Design Notes, no. 37, 18 Feb. 2020, https://pod.link/designnotes/episode/34608799b5dbd2ae59adea29b4b3f5f4.

6 Boellstorff, Tom. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton Univ Press, 2015.

7 “Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction — Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts.” ISO, ISO/TC 159/SC 4, Mar. 2018, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-11:ed-2:v1:en.

8 Spradlin, Liam, and Rob Giampietro. Design Notes, no. 25, 14 May 2019,

https://pod.link/designnotes/episode/53b13783a15dfb8556137f49b19e7e45.