In the most recent Doubleshot newsletter, I wrote a bit about a fountain here in Zürich and how its decorative elements contribute to the interfacial nature of the built environment. In researching the fountain, I found a lot more information about its history, including the stoneworker who originally built its central column and who—at the time of writing—was listed as “unknown” even in Zürich’s own art inventory. I wanted to share all that history here, too.

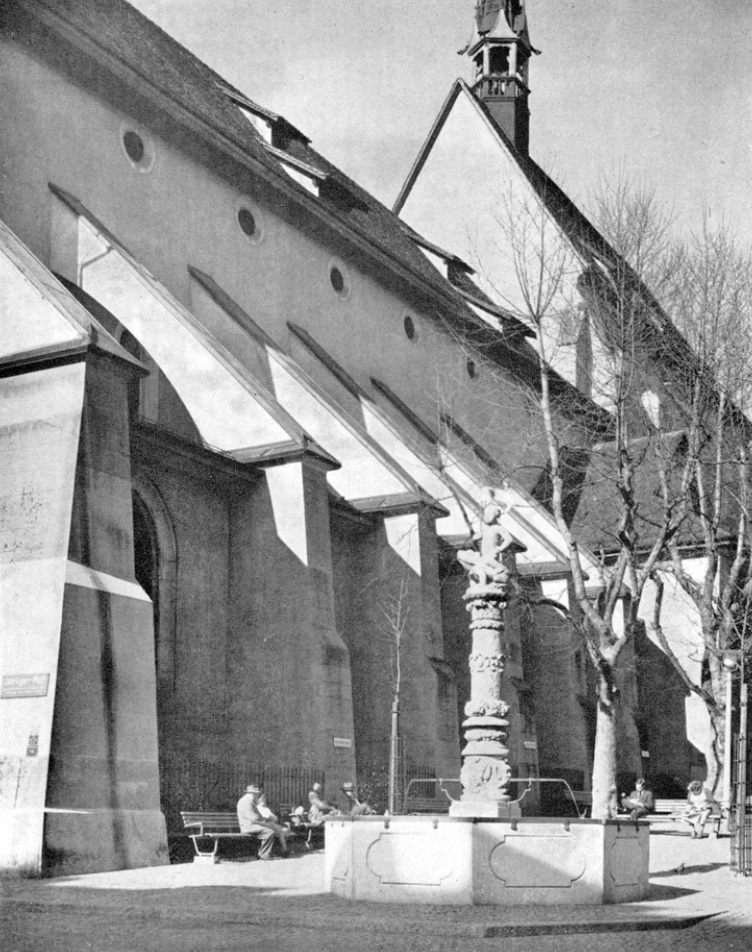

On a cloudy early-autumn morning in Zürich, at the edge of the Altstadt, not too far from where I live, hundreds of huge, dense rose blossoms are being cut from their stems. The red, orange, yellow, pink, and white flowers, each nearly as big as a tennis ball, are gathered up and dumped into the clear water of an octagonal pool at the corner of the Prediger church next to Zürich’s central library. The heavy rose blossoms bob with improbable ease at the top of the water even as two long spouts, jutting from the sides of a central column, babble streams of water down to the pool below. On top of the column, about three meters off the ground, there sits a statue of a boy riding on top of a giant frog and carrying a banner. This is the Froschauerbrunnen or Froschauer fountain in English.

The boy riding the frog is a symbol for Christoph Froschauer, whose name is shared by the fountain itself and whose frog signet (“Frosch” in German) is the motif of several nearby shops along the Froschau-gasse (Froschau alley). Froschauer’s sixteenth-century printing operation in Zürich was responsible for the first printing of the Zwingli Bible translation—the book’s first full translation to German—and thus part of the history of the Reformation in Zürich, which would spread across Switzerland. The printing house would eventually evolve into the Swiss printing giant Orell-Füssli, responsible not just for books but for printing Switzerland’s banknotes as well.

Froschauer started his printing operation in the former Barfüsserkloster (approximately “cloister of the barefooted” in English, referring to an order of Franciscans who don’t wear shoes). It was dissolved as a Franciscan friary in 1524 following the reformation in Zürich. It was there, seven years later (coinciding with Ulrich Zwingli’s death), that the Zwingli (or Zürich) Bible would be published for the first time.

The Froschauerbrunnen’s original sculptor, Balthasar Bingiser, erected the central column of the fountain in the former cloister fifty-four years later, in 1585, on commission from Froschauer’s nephew, who had taken over the printing operation after his uncle’s death. The printing house’s main operations were by then located in the former Convent of St Verena—now the Frosch Cinema—which had been acquired by Froschauer in 1551.

There’s little extant record of Balthasar Bingiser. The trail is made harder to follow by inconsistent records of the 16th-century stoneworker’s name. I first came across the name in a record of renovations made to historical public artworks in Zürich for 1958–59, the Zürcher Denkmalpflege. There, he’s listed as Bingiser, while he’s known elsewhere as Bingesser or Balthasar Steinmann (reflecting his profession). All three names were listed in volume 2 of 6,722 Deutsche Künstler der Renaissance, while another source calls him Andreas Balthasar Steinmann. This book records that Bingiser was born in St. Gallen in 1550 and likely died there in 1610. It also notes that he worked on the fountain in both 1585 and 1589, either adding the original frog signet on top after its initial construction or moving the column to the new printing house. Other sources (like this PhD thesis by Claudia Reeb on cantilevered facade extensions near Lake Constance) suggest that he didn’t die until 1615 and was a carver rather than a sculptor. This calls into question whether he added the original frog signet on top or if he instead only completed the column with a sculptor adding the signet afterward.

Either way, we know that the signet was added between 1585 and 1837 because it was there before the fountain’s central column was moved (in 1837) to a new basin at Zähringerplatz near its current home.

In the late 1950s, it was rebuilt again at the corner of the church where it now stands and given a new copy of the Froschauer signet on top, sculpted by Otto Münch.

The components of the fountain have been moved, recontextualized, remade, and exchanged over more than four centuries of history, and they’re crafted from even older materials: the central column is crafted from porous yellow limestone. Its glacial origin lies in the special “Pierre jaune” (yellow stone) of Neuchâtel, which is over 130 million years old. The basin is made from 145 million-year-old limestone from the canton of Solothurn.

Still, the fountain remains recognizable—not just as itself but as one of the many public water sources in one of the world’s most densely fountained cities (Zürich has over 1,200).

I’ve always been fascinated by the potential hidden histories of old things, and when I pass by the Prediger church, I often think how many people have stopped for a sip at the fountain, sat on its edge, or thrown roses into its basin. It’s an enduring piece of the interface of Zürich, a piece of the built environment that impacts how people in the city experience life.